http://stephenjdubner.com/journalism/101899.html

Selected journalism by Stephen J. Dubner

"I Don’t Want To Live Long. I Would Rather Get The Death Penalty Than Spend The Rest Of My Life In Prison"

Ted Kaczynski talks about life in jail, his appeal plans and his brother David, who still struggles over the decision to turn in the Unabomber

By STEPHEN J. DUBNER

October 18, 1999

There is probably never a good time to ask the question–Tell me, do you consider yourself insane?–but when the time comes, Ted Kaczynski responds without hesitation. "I’m confident that I’m sane, personally," he says. "I don’t get delusions and so on and so forth…I mean, I had very serious problems with social adjustment in adolescence, and a lot of people would call this a sickness. But it would have to be distinguished between an organic illness, like schizophrenia or something like that."

He is sitting on a concrete stool in a concrete booth with windows made of reinforced glass. When he was first led in, his wrists were handcuffed behind his back. Facing forward, he squatted down so a guard could remove his cuffs through a slot low in the door. This is how things are done at the federal "Supermax" prison in Florence, Colo., where he has been since last spring and may well remain for the rest of his life.

His voice is nasal and singsongy, full of flat Chicago vowels. He is 57, his hair and beard trimmed close, and his upbeat manner hardly resembles that of the man who three years ago was marched out of his tiny Montana cabin and into infamy. He makes constant eye contact, laughs easily and often; when it’s time for a photograph, he jokingly pops out a fake front tooth, as if to parody the deranged mountain-man image he inhabits in the public’s mind. He is, for the most part, affable, polite and sincere. It would almost be easy to forget that he mailed or delivered at least 16 package bombs and then logged the results with the glee of a little boy tearing the wings off a fly. Over the course of 18 years, the Unabomber killed three people and wounded 23 more.

When he was arrested, Kaczynski was widely assumed to be insane. But he will not tolerate being called, as he puts it, "a nut," or "a lunatic" or "a sicko." He says he pleaded guilty last year only to stop his lawyers from arguing he was a paranoid schizophrenic, as had been the diagnosis by court-appointed psychiatrists.

While the world might take some comfort in attributing Kaczynski’s deeds to illness rather than ill will, he is actively opposed to lending such comfort. He has written a book, Truth Versus Lies (to be published by Context Books in New York City), its chief aim is to assert his sanity. The book does not address the Unabomber crimes (nor does Kaczynski in person, for he is seeking a retrial and doesn’t wish to damage his slim chances), but it is the most thorough accounting of his life to date.

The book is also Kaczynski’s counterattack against his brother David. It was David, of course, who turned Ted in, at the urging of his wife, Linda Patrik, the woman who had come between them years earlier. After Ted’s arrest, David was instantly lauded as a sort of moral superhero for sacrificing his beloved if troubled brother. Not surprisingly, Ted finds fault with this scenario. David’s decision to turn him in, he says, was less a moral or lawful one than a way to settle a perversely complicated sibling rivalry. Beneath David’s love for him, he argues, lay "a marked strain of resentment," and "jealousy over the fact that our parents valued me more highly."

"It’s quite true that he is troubled by guilt over what he’s done," Ted writes, "but I think his sense of guilt is outweighed by his satisfaction at having finally gotten revenge on big brother."

There is, it should be said, a certain lack of perspective in Ted’s writing. After all, it was he, not David, who sent the bombs. Still, the original tale had been so much neater: the evil, deranged brother and the righteous, heartbroken brother who put a killer out of commission. As it turns out, the Kaczynski tragedy is more Greek than American, a morally complicated tale in which even the most righteous intentions have created shadows that will haunt all the players for the rest of their lives.

In the wake of the Unabomber’s arrest, as David simultaneously lobbied for Ted’s life and reached out to Ted’s victims, he and Linda struck me as extraordinary. They seemed to have stumbled into an impossible situation and acted honorably at every turn. Several months ago, I contacted them to talk about the price of morality–that is, the cost they have paid for committing a deeply difficult act. Because they have sold the book and film rights to their story (the money, they say, will largely go to a fund for bombing victims), certain aspects of their lives are off limits, but otherwise they were forthcoming and frank.

As publication of Ted’s book neared, however, what became even more intriguing than the consequences of their moral act were the motivations behind it. So in August, I wrote to Ted; I wanted his take on the tortured dynamic between the two brothers and the woman who has played such a catalytic, though overlooked, role in their story. (David and Linda were upset when the article shifted in this direction, and eventually stopped participating.)

Ted, as it turned out, was more than eager to talk about David. And about pretty much everything. The life of a notorious prisoner, he admits, has its advantages. He lives on "Celebrity Row," a group of eight cells protected from the prison’s general population. His cell is equipped with a television set (he says he rarely watches) and a light switch, which allows him to stay up at night reading (he has gift subscriptions to the Los Angeles Times, the New York Review of Books, the New Yorker and National Geographic) or writing (answering letters or preparing legal papers). He goes to bed around 10 p.m. and wakes up before 6 a.m., when breakfast is delivered. "The food here, believe it or not, is pretty good," he says. He showers only every other day ("I have sensitive skin") and several days a week is allowed a 90-minute recreation period–the only time he has contact with the other "celebrity" prisoners. "These people are not what you would think of as criminal types," he says. "I mean, they don’t seem to be very angry people. They’re considerate of others. Some of them are quite intelligent."

Among them, he says, are Ramzi Yousef, the mastermind of the World Trade Center bombing, and Timothy McVeigh. One can only imagine this bombing trio’s conversations. Kaczynski says McVeigh (who has recently been transferred to another prison) lent him one of the most interesting books he’s read lately, Tainting Evidence: Inside the Scandals at the FBI Crime Lab, by John F. Kelly and Phillip K. Wearne. "I mean, I knew from my own experience that they were crooked and incompetent," Kaczynski says, shaking his head and laughing. "But according to this book, they’re even worse than what I thought."

Contacting the FBI, he says, was only the beginning of his brother’s betrayal. By arguing that Ted should not be sentenced to death on account of mental illness, David committed a dual sin: labeling Ted crazy and dooming him to an utterly unnatural existence. "He knows very well that imprisonment is to me an unspeakable humiliation," Ted writes in Truth Versus Lies, "and that I would unhesitatingly choose death over incarceration."

At one point, I ask Ted what he would have done had their roles been reversed, had Ted suspected David of being the Unabomber.

"I would have kept it to myself," he says.

"Is that what you feel he should have done?"

"Yeah."

When I ask Ted what he would say to David if he were in the room now, he answers, "Nothing. I just wouldn’t talk to him. I would just turn my back and wouldn’t talk to him."

David, who lives in upstate New York and works as a counselor at a teenage-runaway shelter, says he still loves his brother. He has written him repeatedly, offering at least one apology, but Ted has not answered. In order to gain forgiveness, Ted writes, David must renounce the "lies" he has told about Ted, leave his wife and remove himself from modern society. "If he does not redeem himself," Ted adds, "then as far as I am concerned he is the lowest sort of scum, and the sooner he dies, the better."

It is as awkward to face the gulf between these two brothers as it is difficult to overestimate the depth of feeling that once passed between them. Ted’s life was steeped in rejection, isolation and anger; through it all, his younger brother was the only person ever to connect with him.

David’s feelings for Ted, in fact, bordered on worship. He was particularly smitten by Ted’s belief that modern man was being corrupted by society in general and technology in particular. "Knowing him as I do," Ted writes, "I am certain that if Dave had known of the Unabomber before 1989"–the year David moved in with Linda Patrik–"he would have regarded him as a hero."

David adamantly disputes this–he deplores violence, he says–but he doesn’t seem surprised to hear Ted say it. "I think every person is a mystery, and it’s strange to me that a person I grew up with and was very close with remains one of the biggest mysteries of all." David’s manner is as gentle as Ted’s is brisk, and he speaks with a great earnestness. (The teenagers he counsels call him Mr. Rogers.) When he talks about his brother, however, his voice is full of resignation, the sort felt by someone who has watched a relationship curdle beyond recognition.

The Boys Together

Ted and David’s parents, Wanda and Theodore R. Kaczynski, were atheists, working-class intellectuals who valued education and dearly wanted their sons to succeed on a higher plane.

Ted proved to be exceptionally bright from an early age. He was generally happy, he writes, until he was about 11. That was when he skipped the first of two grades in school, which led to his entering Harvard at the age of 16. At school he was painfully awkward around his older classmates. At home he sulked, and his parents, he says, railed against his antisocial behavior, calling him "sick" and "a creep." He began to despise them, especially Wanda, who he felt treated him more like a trophy than a son. "I hate you, and I will never forgive you, because the harm you did me can never be undone," he would write her more than 30 years later. (Through David, Wanda declined to be interviewed for this article.)

David Kaczynski, seven years younger, had an easier time of things. He too was bright–he would go on to study literature at Columbia University–and he was far more socially adept.

The brothers got along fairly well, although Ted admits to taking out his teenage frustrations on David. Nevertheless, it was Ted whom David most admired, especially as Ted began to speak about abandoning civilization to live in the wilderness. The boys’ father often took them on hikes outside Chicago, and Ted read extensively about nature, wondering what it might be like to live beyond the reach of the modern world.

At Harvard, Ted felt socially isolated by other students. He recalls that "their speech, manners, and dress were so much more ‘cultured’ than mine." There was an even greater unease in Ted’s life; he suffered from what he calls "acute sexual starvation." Sexual references run throughout his book, and although he never ties them into a knot, one cannot help wondering if sexual frustration was his main despair. As an adolescent, he recalls, "my attempts to make advances to girls had such humiliating results that for many years afterward, even until after the age of 30, I found it excruciatingly difficult–almost impossible–to make advances to women… At the age of 19 to 20, I had a girlfriend; the only one I ever had, I regret to say." According to a psychiatric report compiled before his trial, Ted, while in graduate school at the University of Michigan, experienced "several weeks of intense and persistent sexual excitement involving fantasies of being a female. During that time period, he became convinced that he should undergo sex-change surgery."

In the face of such constant sadness and humiliation, Ted Kaczynski eventually decided he would live out his life alone in the wilderness. His retreat to the Montana mountains could simply be viewed as an embrace of a desire he harbored much of his life. Or it could be viewed as a rejection of the world that had rejected him–a world full of purposeful academics and scientists, of happily married couples, of people who weren’t humiliated by daily social interaction–and that would someday pay for its ease.

Growing Apart

When asked about the fondest memories he holds of David, Ted cites a day in the early 1970s in Great Falls, Mont. David had moved there first, after college, and was working as a copper smelter. Ted was building his cabin on land the brothers had bought together outside Lincoln. One day, Ted recalls, they took their baseball gloves to a park. "We were as far apart as we could get and still reach each other with the ball," Ted says, smiling, as if lost in the moment. "We were throwing that ball as hard as we could, and as far as we could… And so we were making these running, leaping catches. We made more fantastic catches that day than I think we did in all the rest of our years together."

Their bond now was perhaps as strong as it would ever be. They were a pair of anti-careerist Ivy League grads united by their love of the outdoors–and also, frankly, by their failure at romantic love. David had been only slightly more successful with women than Ted. He had already decided that there was only one woman he could ever love–her name was Linda Patrik–and though they had a few dates during college, things didn’t work out.

In Great Falls, Ted often spent the night at David’s apartment. One day, while David was not at home, Ted came across some letters from Linda, whom Ted had never heard David mention. "They were in a drawer," Ted writes, "not lying out in the open, and I knew that he would not want me to read them, but I read them anyway… Why did I do it? I was full of contempt for him, and when you have contempt for someone you tend to be disregardful of his rights."

Ted thrived on his brother’s adulation but was also "disgusted" by it, he writes. While they shared a disdain for materialism and an "oversocialized" lifestyle, Ted considered David undisciplined, physically and intellectually lazy. He also felt David was prone to manipulation, especially by women–as Linda Patrik’s letters seemed to illustrate. "The letters were not very informative," he writes, "but they did make this much clear about Dave’s relationship with Linda Patrik: He had a long-term crush on her; his relationship to her was servile." Ted saw David, derisively, as more companion than mate to Linda, "a shoulder for her to cry on."

David and Linda had grown up together in Chicago, and he had never given up on her. They kept in touch while David lived in Montana, and throughout the 1970s, as he taught high school English in Iowa, wrote an unpublished novel and drove a commuter bus near Chicago. But Linda eventually married another man. Faced with this reality, David slipped off to the wilderness–interestingly, not to Ted’s Montana mountain area but to the Big Bend desert region of western Texas. He had $40,000 in savings and, like Ted, a vague plan to spend the rest of his years alone.

He lived in a fortified hole in the ground called a pit house, with no plumbing or electricity. He kept writing but was mainly, according to a friend, "a lost, searching, unhappy soul." He and Ted wrote each other frequently, extremely tender at times but just as often engaged in brittle clashes of ego. "If that story is typical of your previous writing," Ted wrote after David sent him some of his fiction, "then it’s obvious why no one wants to publish your stuff–it’s just plain bad, by anyone’s standard."

In 1982 Ted broke off communication with his parents. Given his brand of terrorism, the breakup’s "proximate cause," as he puts it, was ironic: he was annoyed by the packages of food and reading material his mother mailed him.

For several years, David was Ted’s only link to the family and seemingly the only person in a position to mediate his growing anger. Today David will not say when he began to suspect that Ted was mentally ill, only that "clearly he has had very serious mental and emotional problems."

In September 1989, David wrote Ted to say he was leaving the desert. Linda Patrik had divorced, and after she visited him in Texas, David decided to move with her to Schenectady, N.Y., where she taught philosophy at Union College.

Ted’s response had the tone of a scorned lover, or a deposed guru. "If you don’t irritate or disgust me in one way," he wrote, "then you do so in another… And now, to top off my disgust, you’re going to leave the desert and shack up with this woman who’s been keeping you on a string for the past 20 years." He continued, "I can pretty well guess who the dominant member of that couple is going to be. It’s just disgusting. Let me know your neck size–I’d like to get you a dog collar next Christmas."

He added that he wanted nothing more to do with David, ever, then signed off with a typically manipulative flourish: "But remember–you still have my love and loyalty, and if you’re ever in serious need of my help, you can call on me."

It is tempting to interpret Ted’s anger as a reaction not specifically against Linda–he had never met her–but against his acolyte’s attainment of something he had spent his life without: a woman.

The following summer, David and Linda were married in a Buddhist ceremony in their backyard. Ted did not attend. Two months later, David’s father became ill with late-stage lung cancer. David returned to Chicago; driving home from the hospital after a radiation treatment, father and son had a long, cleansing talk. That night Theodore R. Kaczynski gave David his gold watch; the next day he shot himself.

Ted did not attend his father’s funeral either. By this point, Linda Patrik, having read Ted’s letters to David, recognized that her brother-in-law was trouble. According to the Journal of Family Life, a small Albany, N.Y., publication, Linda forbade David ever to let Ted into their house; she went so far as to warn her father in Chicago that if for some reason Ted were to come to his door, he was to be turned away. She took some of his letters to a psychiatrist, who judged Ted to be paranoid and possibly dangerous. She and David inquired about having him institutionalized, but were told that would be impossible unless Ted were to volunteer. Or unless he had committed acts of violence.

He had done so, of course, and would continue. But David had no inkling–and, as Ted’s still reverent little brother, no desire to have an inkling–that Ted might be the Unabomber. It was Linda who first raised the possibility. In September 1995, when the Washington Post and the New York Times published the Una-bomber’s "manifesto," she cajoled David into reading it. After negotiating with the FBI and deliberating with Linda (one keenly senses she herself might have turned Ted in, had David refused), David told the authorities where they would find his brother.

Life After the Decision

Linda and David still live in Schenectady. They bought their handsome, low-ceilinged, blood-red house–built in 1720–just before the Unabomber was unveiled. Linda now wishes they could live outside the city, away from curiosity seekers who want to see the home of the Unabomber’s brother. On the summer weekend I visited, most of their things were still in boxes. They had just returned from sabbatical and were soon heading out to a monthlong Buddhist seminar.

Linda, 49, and David, 50, have both gone gray since the 60 Minutes interview in which they pleaded that Ted’s life be spared and announced they would take no money, reward or otherwise, generated by this case. Their marriage has grown stronger these past years, they both say, but when asked about Unabomber-induced tensions, Linda promptly ticks off items on her list. While she was the catalyst for capturing the Unabomber, for instance, most reporters wanted to speak only to David. "Then I get to feel envious," she says, "and David gets credit for turning in his brother, and I don’t." She was also jealous of how some journalists, especially those young and female, regarded her husband, "gazing at him with puppy-dog eyes and hanging on every word." Did her philosophy students ever question her about the moral dimensions of her dilemma? "No, no, no. They come to me and say, ‘Oh, your husband’s so wonderful, you’re so lucky to be married to such an ethical man.’" She sticks a finger down her throat and pretends to gag. David laughs uncomfortably. As she speaks, he listens, careful not to interrupt; when it is his turn, he seems to tread lightly.

I had expected, I must admit, a more united front. Only now do I realize their desire to turn Ted in may not have been unilateral: Linda was afraid of this man she had never met, while David loved at least a part of him. That their marriage could survive such pressure–even before the media wave–says a lot about it.

Alone, David is looser. He plays baseball in an over-30 league, and one morning he took me to his game. (He played first base and pitched, batting two for four.) Baseball, he says, is the one thing that allows him to forget the ordeal, if only for a few hours. On the drive home, he spoke passionately about his love of nature, literature and philosophy. Before long, though, his mind returned to the Unabomber. Soon after his brother’s arrest, he says, "I had a depressive realization that I don’t know if I’ll ever really feel carefree again, ever come upon those moods where you just feel unalloyed delight and joy." Before his discovery that Ted was the Unabomber, he adds, "ethical questions weren’t that important to me. I was more interested in trying to break through and find the transcendental. But now I have all kinds of questions about other things. I thought I knew the difference between right and wrong." Clearly, that difference has been forever muddied–for his decision to turn in the Unabomber was the right thing to do, as wrong as it feels to have imprisoned his brother.

And now comes Ted’s book, charging that David’s decision was in some part based on resentment. "I think he’s wrong there," David says, while acknowledging that "there have been times when I felt some resentment of Ted" and that Ted sometimes made him "very angry."

David, it seems likely, will forever wrestle with the horrible bind his murderous brother put him in. Balancing his devotion to Ted with a devotion to the aftermath of Ted’s actions, he is the opposite of a kid who begs his parents for a puppy and then abandons all custodial duties. Last year, for instance, he spent months lobbying Congress (unsuccessfully) to exempt the Unabomber reward from taxes so the bulk of it could go to the victims’ fund he and Linda established. Yet David’s life, oddly, may be richer now than it has ever been. As a man who has long existed in the shadow of someone else–first his brother, then his wife–he at last finds himself at the center of things. There are humanitarian awards to accept, anti-death penalty interviews to give, victims’-rights speeches to deliver. He has even considered a lecture tour with one of Ted’s victims.

Might he even leave his counseling job for a life of public speaking and advocacy? "Yes," he says, "but I’m leery of making money or celebrity out of this terrible tragedy. On the other hand, it’s an amazing opportunity to be listened to… Obviously, I’m not immune to flattery, and it feels good to get those kinds of strokes from people."

Asked whether he feels guilty for having turned Ted in, David says, "Guilt suggests a very clear conviction of wrongdoing, and certainly I don’t feel that I did wrong. On the other hand, there are tremendously complicated feelings not just about the decision itself but a lifetime of a relationship in which one brother failed to help protect another." Even now, he hopes Ted will one day agree to see him, but when asked whether he has envisioned their reconciliation, he grows quiet. "No, I don’t think it would be helpful," he says after a time. "The future never meets us in the ways we imagine."

Ted Looks to the Future

Ted Kaczynski too enjoys a certain amount of attention these days. He receives mail from sympathizers and admirers. He has accepted an offer to donate his personal papers to a major university’s library of anarchist materials. He wrote a parable for a literary magazine at another university. Speaking with him, one is struck not by the burning anger that characterized his Una-bomber campaign but by a satisfaction that the world, at long last, is treating him like a valuable human being.

His spirits don’t seem particularly low–not nearly as low as the relatives of his victims might like them to be. To me, in fact, he seems optimistic about life in general.

"Well, obviously I’m not optimistic about life in general," he says. "If I were, then maybe you would have a case for concluding that I was mentally ill.

"Let me try to explain it this way," he continues. "When I was living in the woods, there was sort of an undertone, an underlying feeling that things were basically right with my life. That is, I might have a bad day, I might screw something up, I might break my ax handle and do something else and everything would go wrong. But…I was able to fall back on the fact that I was a free man in the mountains, surrounded by forests and wild animals and so forth.

"Here it’s the other way around. I’m not depressed or downcast, and I have things I can do that I consider productive, like working on getting out this book. And yet the knowledge that I’m locked up here and likely to remain so for the rest of my life–it ruins it. And I don’t want to live long. I would rather get the death penalty than spend the rest of my life in prison."

To get the death penalty, Kaczynski will first have to gain a retrial, which he knows is improbable. At a new trial, he would represent himself, but he won’t discuss the strategy he might employ.

What would seem most likely is for him to argue that, essentially, desperate disease requires a desperate cure. As the Unabomber manifesto put it, "The Industrial Revolution and its consequences have been a disaster for the human race." In the Unabomber’s mind, society was in desperate need of a brave and brazen savior who wouldn’t let murder stand in his way. "Well, let me put it this way," Kaczynski says. "I don’t know if violence is ever the best solution, but there are certain circumstances in which it may be the only solution."

To anarchists who advocate violence, Kaczynski has become a hero. He is flattered but notes that "a lot of these people are just irrational." What Kaczynski wants is a true movement, "people who are reasonably rational and self controlled and are seriously dedicated to getting rid of the technological system. And if I could be a catalyst for the formation of such a movement, I would like to do that."

Ted Kaczynski, king of the anarchists. It is a measure of his self-importance–and cruelty–that he envisions such a role as his reward for blowing people up.

Toward the end of our interview, I ask Kaczynski what he would do if, against all odds, he should someday get out of prison. He mentions an anarchist in Oregon with whom he has corresponded. "He has given some talks at colleges about technology and about the Unabomb case," Kaczynski says, "and he’s had a very positive response. And if he can get an audience, I could get one much more easily, now that I’ve been publicized."

And what, I ask Kaczynski, would he tell people, so they wouldn’t worry about the Unabomber’s being at large?

He laughs at the question and shoots me a look: You just don’t get it, do you? "Well, I don’t know that I would have to relax them," he says. "Just let them worry."

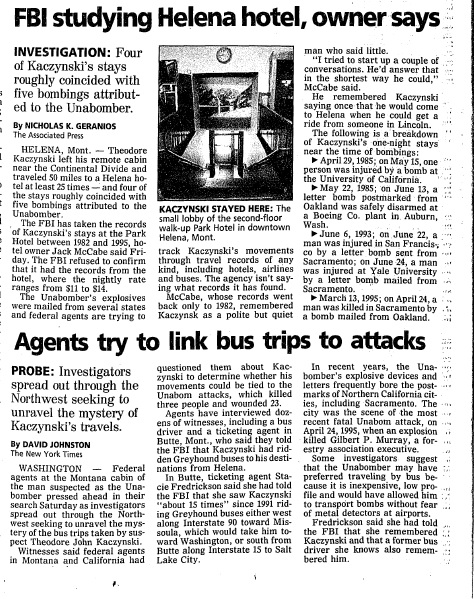

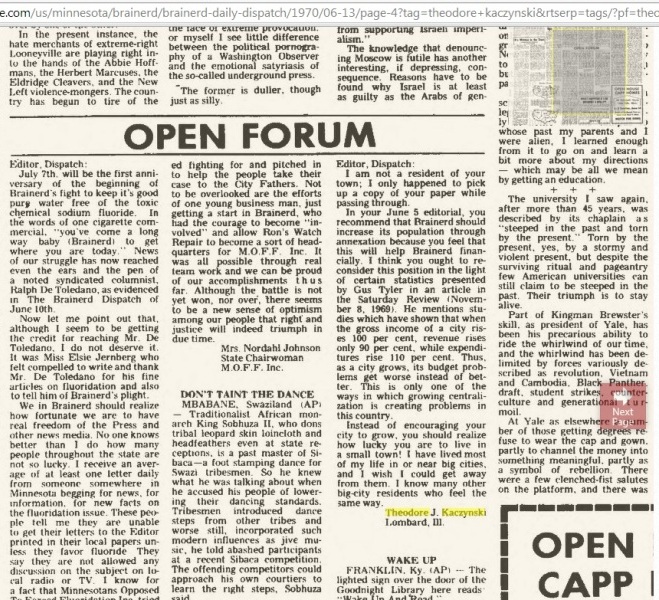

This sight has the forensic evaluation which discussed some dates and places.

1. "In reviewing available background information on.. it was useful to review his two lengthy autobiographical documents. At the time he went to Harvard and became involved in a psychological study of students there, he was asked to write the first autobiography." Written in 1959.

(I would like to see this document to compare it to the Mad is the word essay from EAR.)

2. June 1969 left Berkeley and moved to Lombard, Il.

3. Summer 1969 traveled with David.

4. Summer 1970 David moved to Great Falls, MT.

5. End of 1970 worked for Abbot Consultants in Elmherst, Il

6. Summer 1971 Build cabin in MT

7. Late 1972 to Dec. 1973 worked in Chicago and Salt Lake City, UT.

8. June 1973 returned to his cabin in MT.

9. September 1974 worked for three weeks as gas station attend in Montana.

10. January 1975 he traveled to Oakland, CA.

11. March 1975 he returned to cabin in MT.

12. May 1976 or (*June 1976) returned to Chicago in search of work (*according to Ellen article it was July when he was fired. Worked at Foam Cutting Engineers.

13. Sept. 1978 to March 1979 employed by Prince Castle.

14. March 1979 lived with parents in Lombard, Il

15. Summer 1979 returned to cabin in MT.

16. Mid-1980 traveled to Canada.

http://www.thesmokinggun.com/file/unabo … ait-madman

http://www.michigandaily.com/content/he … -unabomber

It’s been 43 years since Ted Kaczynski first stepped onto the University of Michigan campus.

Since then, he’s spent 18 of those 43 years – from 1978 to 1995 -mailing bombs. He’s killed three people, wounded 29 and received four life sentences without parole.

But he still describes his five years at the University as among the worst in his life.

"My memories of the University of Michigan are NOT pleasant," he wrote me in a letter dated Jan. 16.

Attached to the letter, he included a hand-copied excerpt from his 1979 unpublished autobiography on extra-long legal paper.

"So I went to the U. of Michigan in the fall of 1962, and I spent five years there," he wrote. "These were the most miserable years of my life (except for the first year and the last year)."

When Kaczynski entered the University, he was a precocious, solitary mathematics student whose brilliance his undergraduate education at Harvard had not yet revealed. It was 1962. He was 20 years old. His name was still Ted Kaczynski.

By the time he’d left, it was 1967. He was 25 years old. He had earned a master’s and doctorate in mathematics. And he’d developed an identity with a different name. He was the Unabomber.

The University was not Kaczynski’s first choice for graduate work. He also applied to the University of California at Berkeley and the University of Chicago. All three schools accepted him. None initially offered a student-teaching position or financial aid.

His grades at Harvard were unexceptional, especially for someone who had entered the world’s most prestigious at age 16. In his last year as an undergrad, he scored a B+ in History of Science, B- in Humanities 115, B in Math 210, B in Math 250, A- in Anthropology 122, C+ in History 143 and A- in Scandinavian. Earlier in his career, he earned an embarrassing C in Mathematics 101. He finished with a 3.12 GPA. Those grades may not seem drastically poor – especially given it was a time before rampant grade inflation – but Kaczynski had a 170 IQ at age 10. He was expected to perform better.

The University of Michigan eventually offered him a grant of $2,310 a year to serve as a student teacher. He packed his bags and traveled to Ann Arbor.

His grades at the University marked an improvement from his grades at Harvard. He limited himself to two courses per semester to accommodate his considerable teaching duties.

During his five-year career, he came into his own academically. In a turn around from his struggles at Harvard, Kaczynski’s lowest grade – save a failure in physics – was a B-. He only received four other B’s to go along with his 12 A’s.

His teaching, though, was not up to par. After sitting in on his class on Oct. 12, 1962, an evaluator gave him lukewarm marks: a "good" in categories like subject knowledge but only an "average" in subjects like student participation.

There was one isolated rift with a student, who called him a "really incompetent teacher who did not know his subject." The professors kept a close eye on him for a while. There were no more complaints.

He was the darling of the math department, finishing his master’s degree in 1964.

"Best man I have seen," wrote Math Prof. Allen Shields in a grade evaluation.

"He just seems a little too sure of himself," was Math Prof. Pete Duren’s only complaint.

Maybe he had reason to be. Kaczynski had a habit of solving extremely difficult problems and then publishing them in prestigious journals.

Once, as Math Prof. George Piranian told author Alton Chase, Piranian told his students that he had a problem about a lesser-known mathematical subject called boundary functions that no one had solved. Weeks later, Kaczynski placed 100 handwritten pieces of paper on Piranian’s desk. He had solved the problem.

Kaczynski’s academic prowess peaked with his doctoral dissertation, titled "Boundary Functions." The dissertation was awarded the Sumner Myers prize for the University’s best mathematics thesis of the year, netting Kaczynski $100. A plaque listing his accomplishment is still displayed near the East Quad Residence Hall entrance. If you Google "boundary functions" name now, the third result is an excerpt from Kaczynski’s thesis.

Every professor on his dissertation committee approved it.

"This thesis is the best I have ever directed," Shields wrote in an evaluation form.

Kaczynski’s genius was finally starting to reveal itself.

Something else was, too.

It’s chilling to think that while Kaczynski was at the University – walking down State Street on football Saturdays, sitting in the Diag, taking notes in Angell Hall classrooms – his peers and teachers did not see anything in him that would lead them to believe that he would go on to be one of America’s most infamous terrorists.

In a letter of recommendation to the financial aid office, Shields, perhaps Kaczynski’s strongest supporter, wrote "Mr. Kaczynski is a very pleasant person."

Shortly after Kaczynski’s arrest in 1996, Duren told The Michigan Daily that the math department’s star student was a loner but was always polite.

Asked by the Daily three decades later whether he would have thought the 1967 version of Kaczynski could have been Unabomber, Piranian said he would have answered with a "categorical no."

As is the case among his fellow classmates, many peers have had trouble even remembering him. It appears that only one, a fellow graduate student at the University of Michigan named Joel Shapiro, has been quoted in major media sources.

On an evaluation for a class for which he awarded Kaczynski a B+, Piranian wrote: "Has ability, lacks fire."

Certainly there was nothing that would have foreshadowed his rise to the position of the most notorious of the University’s 425,000 living alumni (sorry, Jack Kevorkian).

It appears Kaczynski was so quiet that no one noticed him. His meticulous concentration on academics completely consumed him?

Then what made him become the Unabomber?

If you read the selection of Kaczynski’s unpublished autobiography he sent me, you’d think that it was the incompetence of his professors at the University.

"The fact that I not only passed my courses (except one physics course) but got quite a few A’s, shows how wretchedly low the standards were at Michigan," he wrote.

He later describes how professors often showed up to class unprepared and how they could not complete some of the proofs they assigned.

"The atmosphere to me felt extremely sordid – most instructors and most students did only what they had to do – there was no interest or enthusiasm or even any sense of responsibility about doing a good job," he wrote.

The poor teaching had some psychological effects, his writings suggest.

"Sloppy, careless, poorly organized teaching can destroy the morale of many students," Kaczynski wrote.

Nonetheless, there is no compelling evidence that the professors’ incompetence had more than a slight hand in leading him in his descent into madness.

The Unabomber would later take his anger out on all of academia, though for more complicated reasons than poor teaching. His bombing spree started at Northwestern University in May 1978.

Kaczynski’s rampage also included bombs sent to Yale University, Vanderbilt University, the University of Utah in Salt Lake City and the University of California at Berkeley, among others. The moniker Unabomber is the media’s version of the FBI’s code name for him, UNABOM, which stands for university and airplane bomber. The latter is derived from his bombing of several airline officials in 1978 and a bomb he put in the cargo hold of a commercial airplane in 1979. Smoke seeping from the bomb on plane forced the plane to make an emergency landing, but a faulty timing mechanism prevented the bomb from exploding. Authorities said it had the necessary firepower to destroy the plane.

One of his bombs was intended for University Psychology Prof. James McConnell in 1985. McConnell was not hurt. His assistant, Nicklaus Suino, sustained flesh wounds to his arm and abdomen. The link between Kaczynski and McConnell, who died in 1990, is unclear. They never met.

Many suspect that he targeted McConnell after reading his textbook, "Understanding Human Behavior," which clashed with many of the Unabomber’s beliefs in the "Manifesto" he published in 1995.

The manifesto claims the Industrial Revolution led to "widespread psychological suffering" and said technology would cause "social disruption and psychological suffering."

There is also no evidence that Kaczynski began developing those left-wing thoughts at the University of Michigan, though he later claimed he was mailing the bombs to advance his social ideologies. It wasn’t until three years later that those beliefs began to permeate his thoughts. In 1970, he wrote a response to a book by Jacques Ellul called "The Technological Society."

Despite the politically charged atmosphere on campus at the time, Kaczynski never mentioned any political beliefs, radical or otherwise, Duren said.

"If he’s the Unabomber, that’s a different person than the one I knew," he said.

So if it wasn’t his dystopian fears that wrangled his shadowy genius from math to murder, what was it?

Near the end of his years in Ann Arbor, Kaczynski moved into a rooming house at 524 South Forest Ave.

At night, he was tormented by the sounds of a couple having sex through the thin walls. Kaczynski, who was in his mid-20s at the time, had begun to suffer from sexual repression.

In a fit of naivete, he reported the sounds to the University, which, of course, took no action. At the time, he also grew convinced his landlord had turned others against him. He had trouble fitting in at the University. He was anti social, disdained others and showed little willingness to communicate with peers.

He began to have nightmares. In them, he was constantly hounded by organized society, which he usually manifested as psychologists. The psychologists tried to control his mind with tricks, causing him to grow angrier and angrier. Eventually, this man who did not bend – not even in the world of dreams – would break. He would kill the psychologists as well as their allies, and afterward, feel relief and liberation. Then, though, his victims would spring back up. As time went by, he grew more successful in keeping them dead by concentrating hard enough.

According to a detailed psychological profile done of him by psychiatrist Sally Johnson, Kaczynski experienced a period of a few weeks in the summer of 1966 during which he was constantly sexually aroused.

In a severe twist of logic that is telling of his jumbled thought processes during his time at the University, he reasoned that the only way he would ever be able to touch a woman was to become one himself. Kaczynski began to fantasize about being female.

When he returned to Ann Arbor in the fall, he went as far as to make an appointment at the University Health Center to see a psychiatrist to discuss whether a sex change would be a good choice for him. Kaczynski’s plan was to trick the doctor into believing that the operation wasn’t merely for erotic purposes, but was rather intended to make him into the more feminine person he was destined to be.

As he was sitting in the waiting room, he experienced a sudden change of heart, and instead he lied to the psychiatrist, telling him he had come because he was depressed about the possibility of being drafted into military service.

He deplored the shame sexual cravings had caused him. As he walked away, Kaczynski felt a flood of humiliation. He felt disgusted. He felt like he had lost control of his libido. He felt like he didn’t want to live anymore.

Something snapped.

The Unabomber finally had the answer. He felt like killing the psychiatrist. The very thought improved his mood. He did not care whether he himself lived or died, so maybe it would make him feel better to kill someone else, too.

"Just then there came a major turning point in his life," he later told Johnson. "Like a phoenix, I burst from the ashes of my despair to a glorious new hope."

It was then that he decided to spend his life killing. He would avoid capture in order to continue to kill. Kill. It is easy to imagine the word running through his head as he walked home across campus from the health center. Kill. Kill. It was a thunderclap of clarity. The story arc of his life had revealed itself to him. He must have felt like he had finally worked to the end of some unsolvable proof and was left with a simple answer: kill.

The Unabomber decided he would go to Canada, he later told Johnson. He would hide in the woods with only a rifle to keep him company.

"If it doesn’t work and if I can get back to civilization before I starve then I will come back here and kill someone I hate," he wrote.

Kill.

First he had to get enough money to buy a cabin and some land to carry out his plans of delicious revenge. He graduated from the University in 1967 and was hired as an assistant professor at the University of California at Berkeley.

In 1969, having made enough money to fund the construction of a secluded cabin in the wild of Montana, the Unabomber resigned from his post at Berkeley.

Back in Ann Arbor, the news reached Shields that his former prize student had quit. A concerned Shields sent Berkeley a letter asking what had happened.

"He said he was going to give up mathematics," a professor wrote back. "He wasn’t sure what he was going to do."

THE KACZYNSKI PAPERS

Atop the Harlan Hatcher Graduate Library sits the Special Collections Library in a series of peculiar rooms. Inside, an avalanche of paper decays and the smell of academia taints the air. Buried within is the Labadie Collection, which houses papers on anarchy, socialism, communism and other non-mainstream topics. And buried within that is the papers of Ted Kaczynski.

Kaczynski donated many of his papers to the University in 1999. Now they fill more than 15 boxes. It is open to the public. You can sift through his papers while looking out over the Diag below.

The papers are mostly letters he’s received since his 1996 incarceration. The bulk of the correspondence is supportive. Kaczynski claims he submitted them all to the library without weeding out the negative ones. Some are evangelical, others seek for a piece of notoriety such as an autograph, while others ask for romance. Some assert his innocence. Many are from media such as 20/20, The Roseanne Show and the New Yorker requesting interviews. In one letter, NBC’s Katie Couric congratulates Kaczynski on a 1999 legal victory of his. "I’m sure you’re very busy these days working on your defense," Couric wrote before asking him for an interview, which he did not accept.

There is also a long list of books the FBI found in his Montana when he was arrested. The books include "The Elements of Style," "Field Guide to Rocky Mountain Wildflowers" and "Cossacks and the Raid," among many other obscure titles.

One of the dark green boxes contains a 1996 day planner. Among the sparse entries is on March 7: "Shower change of clothes" it reads. There is nothing until March 12, when the same line is repeated.

http://www.primitivism.com/kaczynski.htm

-Dr. Theodore Kaczynski, in an interview with the Earth First! Journal, Administrative Maximum Facility Prison, Florence, Colorado, USA, June 1999.

Theodore Kaczynski developed a negative attitude toward the techno-industrial system very early in his life. It was in 1962, during his last year at Harvard, he explained, when he began feeling a sense of disillusionment with the svstem. And he says he felt quite alone. "Back in the sixties there had been some critiques of technology, but as far as 1 knew there weren’t people who were against the technological system as-such… It wasn’t until 1971 or 72, shortly after I moved to Montana, that I read Jaques Ellul’s book, The Technological Societv." The book is a masterpiece. I was very enthusiastic when I read it. I thought, ‘look, this guy is saying things I have been wanting to say all along.’"

Why, I asked, did he personally come to be against technology? His immediate response was, "Why do you think? It reduces people to gears in a machine, it takes away our autonomy and our freedom." But there was obviously more to it than that. Along with the rage he felt against the machine, his words revealed an obvious love for a very special place in the wilds of Montana. He became most animated, spoke most passionately, while relating stories about the mountain life he created there and then sought to defend against the encroachment of the system. "The honest truth is that I am not really politically oriented. I would have really rather just be living out in the woods. If nobody had started cutting roads through there and cutting the trees down and come buzzing around in helicopters and snowmobiles I would still just be living there and the rest of the world could just take care of itself. I got involved in political issues because I was driven to it, so to speak. I’m not really inclined in that direction."

Kaczynski moved in a cabin that he built himself near Lincoln, Montana in 1971. His first decade there he concentrated on acquiring the primitive skills that would allow him to live autonomously in the wild. He explained that the urge to do this had been a part of his psyche since childhood. "Unquestionably there is no doubt that the reason I dropped out of the technological system is because I had read about other ways of life, in particular that of primitive peoples. When I was about eleven I remember going to the little local library in Evergreen Park, Illinois. They had a series of books published by the Smithsonian Institute that addressed various areas of science. Among other things, I read about anthropology in a book on human prehistory. I found it fascinating. After reading a few more books on the subject of Neanderthal man and so forth, I had this itch to read more. I started asking myself why and I came to the realization that what I really wanted was not to read another book, but that I just wanted to live that way."

Kaczynski says he began an intensive study of how to identify wild edible plants, track animals and replicate primitive technologies, approaching the task like the scholar he was. "Many years ago I used to read books like, for example, Ernest Thompson Seton’s "Lives of Game Animals" to learn about animal behavior. But after a certain point, after living in the woods for a while, I developed an aversion to reading any scientific accounts. In some sense reading what the professional biologists said about wildlife ruined or contaminated it for me. What began to matter to me was the knowledge I acquired about wildlife through personal experience.

Kaczynski spoke at length about the life he led in his small cabin with no electricity and no running water. It was this lifestyle and the actual cabin that his attorneys would use to try to call his sanity into question during his trial. It was a defense strategy that Kaczynski said naturally greatly offended him. We spoke about the particulars of his daily routine. "I have quite a bit of experience identifying wild edible plants," he said proudly, "it’s certainly one of the most fulfilling activities that I know of, going out in the woods and looking for things that are good to eat. But the trouble with a place like Montana, how it differs from the Eastern forests, is that starchy plant foods are much less available. There are edible roots but they are generally very small ones and the distribution is limited. The best ones usually grow down in the lower areas which are agricultural areas, actually ranches, and the ranchers presumably don’t want you digging up their meadows, so starchy foods were civilized foods. I bought flour, rice, corn meal, rolled oats, powdered milk and cooking oil."

Kaczynski lamented never being able to accomplish three things to his satisfaction: building a crossbow that he could use for hunting, making a good pair of deerhide moccasins that would withstand the daily hikes he took on the rocky hillsides, and learning how to make fire consistently without using matches. He says he kept very busy and was happy with his solitary life. "One thing I found when living in the woods was that you get so that you don’t worry about the future, you don’t worry about dying, if things are good right now you think, ‘well, if I die next week, so what, things are good right now.’ I think it was Jane Austen who wrote in one of her novels that happiness is alwavs something that you are anticipating in the future, not something that you have right now. This isn’t always true. Perhaps it is true in civilization, but when you get out of the system and become re-adapted to a different way of life, happiness is often something that you have right now."

He readily admits he committed quite a few acts of monkeywrenching during the seventies, but there came a time when he decided to devote more energy into fighting against the system. He describes the catalyst:

"The best place, to me, was the largest remnant of this plateau that dates from the tertiary age. It’s kind of rolling country, not flat, and when you get to the edge of it you find these ravines that cut very steeply in to cliff-like drop-offs and there was even a waterfall there. It was about a two days hike from my cabin. That was the best spot until the summer of 1983. That summer there were too many people around my cabin so I decided I needed some peace. I went back to the plateau and when I got there I found they had put a road right through the middle of it" His voice trails off; he pauses, then continues, "You just can’t imagine how upset I was. It was from that point on I decided that, rather than trying to acquire further wilderness skills, I would work on getting back at the system. Revenge. That wasn’t the first time I ever did any monkeywrenching, but at that point, that sort of thing became a priority for me… I made a conscious effort to read things that were relevant to social issues, specifically the technological problem. For one thing, my concern was to understand how societies change, and for that purpose I read anthropology, history, a little bit of sociology and psychology, but mostly anthropology and history."

Kaczvnski soon came to the conclusion that reformist strategies that merely called for "fixing" the system were not enough, and he professed little confidence in the idea that a mass change in consciousness might someday be able to undermine the technological system. "I don’t think it can be done. In part because of the human tendency, for most people, there are exceptions, to take the path of least resistance. They’ll take the easy way out, and giving up your car, your television set, your electricity, is not the path of least resistance for most people. As I see it, I don’t think there is any controlled or planned way in which we can dismantle the industrial system. I think that the only way we will get rid of it is if it breaks down and collapses. That’s why I think the consequences will be something like the Russian Revolution, or circumstances like we see in other places in the world today like the Balkans, Afghanistan, Rwanda. This does, I think, pose a dilemma for radicals who take a non-violent point of view. When things break down, there is going to be violence and this does raise a question, I don’t know if I exactly want to call it a moral question, but the point is that for those who realize the need to do away with the techno-industrial system, if you work for its collapse, in effect you are killing a lot of people. If it collapses, there is going to be social disorder, there is going to be starvation, there aren’t going to be any more spare parts or fuel for farm equipment, there won’t be any more pesticide or fertilizer on which modern agriculture is dependent. So there isn’t going to be enough food to go around, so then what happens? This is something that, as far as I’ve read, I haven’t seen any radicals facing up to.

At this point he was asking me, as a radical, to face up to this issue. I responded I didn’t know the answer. He said neither did he, clasped his hands together and looked at me intently. His distinctly Midwestern accent, speech pattern, and the colloquialisms he used were so familiar and I thought about how much he reminded me of the professors I had as a student of anthropology, history and political philosophy in Ohio. I decided to relate to him the story of how one of my graduate advisors, Dr. Resnick, also a Harvard alumni, once posed the following question in a seminar on political legitimacy: Say a group of scientists asks for a meeting with the leading politicians in the country to discuss the introduction of a new invention. The scientists explain that the benefits of the technology are indisputable, that the invention will increase efficiency and make everyone’s life easier. The only down side, they caution, is that for it to work, forty-thousand innocent people will have to be killed each year. Would the politicians decide to adopt the new invention or not? The class was about to argue that such a proposal would be immediately rejected out of hand, then he casually remarked, "We already have it–the automobile." He had forced us to ponder how much death and innocent suffering our society endures as a result of our commitment to maintaining the technological system–a system we all are born into now and have no choice but to try and adapt to. Everyone can see the existing technological society is violent, oppressive and destructive, but what can we do?

"The big problem is that people don’t believe a revolution is possible, and it is not possible precisely because they do not believe it is possible. To a large extent I think the eco-anarchist movement is accomplishing a great deal, but I think they could do it better… The real revolutionaries should separate themselves from the reformers… And I think that it would be good if a conscious effort was being made to get as manv people as possible introduced to the wilderness. In a general way, I think what has to be done is not to try and convince or persuade the majority of people that we are right, as much as try to increase tensions in society to the point where things start to break down. To create a situation where people get uncomfortable enough that they’re going to rebel. So the question is how do you increase those tensions? I don’t know."

Kaczynski wanted to talk about every aspect of the techno-industrial system in detail, and further, about why and how we should be working towards bringing about its demise. It was a subject we had both given a lot of thought to. We discussed direct action and the limits of political ideologies. But by far, the most interesting discussions revolved around our views about the superiority of wild life and wild nature. Towards the end of the interview, Kaczynski related a poignant story about the close relationship he had developed with snowshoe rabbit.

"This is kind of personal," he begins by saying, and I ask if he wants me to turn off the tape. He says "no, I can tell you about it. While I was living in the woods I sort of invented some gods for myself" and he laughs. "Not that I believed in these things intellectually, but they were ideas that sort of corresponded with some of the feelings I had. I think the first one I invented was Grandfather Rabbit. You know the snowshoe rabbits were my main source of meat during the winters. I had spent a lot of time learning what they do and following their tracks all around before I could get close enough to shoot them. Sometimes you would track a rabbit around and around and then the tracks disappear. You can’t figure out where that rabbit went and lose the trail. I invented a myth for myself, that this was the Grandfather Rabbit, the grandfather who was responsible for the existence of all other rabbits. He was able to disappear, that is why you couldn’t catch him and why you would never see him… Every time I shot a snowshoe rabbit, I would always say ‘thank you Grandfather Rabbit.’ After a while I acquired an urge to draw snowshoe rabbits. I sort of got involved with them to the extent that they would occupy a great deal of my thought. I actually did have a wooden object that, among other things, I carved a snowshoe rabbit in. I planned to do a better one, just for the snowshoe rabbits, but I never did get it done. There was another one that I sometimes called the Will ‘o the Wisp, or the wings of the morning. That’s when you go out in to the hills in the morning and you just feel drawn to go on and on and on and on, then you are following the wisp. That was another god that I invented for myself."

So Ted Kaczynski, living out in the wilderness, like generations of prehistoric peoples before him, had innocently rediscovered the forest’s gods. I wondered if he felt that those gods had forsaken him now as he sat facing life in prison with no more freedom, no more connection to the wild, nothing left of that life that was so important to him except for his sincere love of nature, his love of knowledge and his commitment to the revolutionary project of hastening the collapse of the techno-industrial system. I asked if he was afraid of losing his mind, if the circumstances he found himself in now would break his spirit? He answered, "No, what worries me is that I might in a sense adapt to this environment and come to be comfortable here and not resent it anymore. And I am afraid that as the years go by that I may forget, I may begin to lose my memories of the mountains and the woods and that’s what really worries me, that I might lose those memories, and lose that sense of contact with wild nature in general. But I am not afraid they are going to break my spirit. "And he offered the following advice to green anarchists who share his critique of the technological system and want to hasten the collapse of, as Edward Abbey put it, "the Earth-destroying juggernaut of industrial civilization": "Never lose hope, be persistent and stubborn and never give up. There are many instances in history where apparent losers suddenly turn out to be winners unexpectedly, so you should never conclude all hope is lost. "

http://www.lib.umich.edu/blogs/beyond-r … hotographs

The Ted Kaczynski Papers: FBI Files and Photographs

August 20, 2014

See all posts by Rosemary Pal

Outside of Ted Kaczynski’s cabin near Lincoln, Montana.

The Ted Kaczynski Papers are part of the Special Collections Library’s Joseph A. Labadie Collection which documents the history of social protest movements and marginalized political communities from the 19th century to the present. The Ted Kaczynski papers were acquired in 1998 and the bulk of the collection includes correspondence written to and by Kaczynski since his arrest in 1996. Other materials in the archive include legal documents used during his trial, writings by Kaczynski, clippings and articles, some audiovisual material and FBI files.

Theodore John Kaczynski was arrested by the FBI on April 1996 at his cabin near Lincoln, Montana. He was accused of (and later plead guilty and convicted of) killing three people and injuring 22 in 16 separate bombings between 1978 and 1995. Even before Kaczynski was identified as a suspect, the FBI labeled the case "Unabomb" because the first targets were linked to universities (UNabomb) or airlines (unAbomb).

In 2012 the FBI files were sent by Kaczynski’s lawyers to Special Collections and made part of the archive. These files consist of photocopies of documents confiscated by the FBI during Kaczynski’s arrest at his cabin in Montana in 1996. The contents are mainly photocopies from his journals written in English, Spanish, and a numeric code. The earliest entry is dated 1969 and the last is February 1996. Other documents include photocopies of maps, identification papers, math equations, correspondence with family members and other miscellaneous documents.

The FBI files also contain dozens of photographs taken by agents after Kaczynski’s arrest and used during his trial. The photographs show the outside area of Kaczynski’s cabin, the land surrounding the cabin and downtown Lincoln, Montana and photos of the famous cabin along with its contents. Some photos are of books, rifles and some bomb making materials. Below are some examples of pictures found in the FBI files in the archive:

Ted Kaczynski’s mailbox in Lincoln, Montana

Ted Kaczynski’s mailbox near Lincoln, Montana.

Inside Kaczynski’s small cabin including books, hunting rifles and other items

Inside Kaczynski’s small cabin including books, hunting rifles and other items.

Books found in Kaczynski’s cabin on topics such as chemistry, nuclear weapons and botany

Books found in Kaczynski’s cabin on topics such as chemistry, nuclear weapons and botany.

More books on the history of the Middle Ages, Peru, Mexico and Russia and other topics

More books on the history of the Middle Ages, Peru, Mexico and Russia and other topics.

Kaczynski’s arrest on April 3, 1996 at his cabin in Lincoln, Montana

Kaczynski’s arrest on April 3, 1996 at his cabin near Lincoln, Montana.

For access and more information on the Ted Kaczynski Papers at Special Collections please send an email to special.collections@umich.edu.

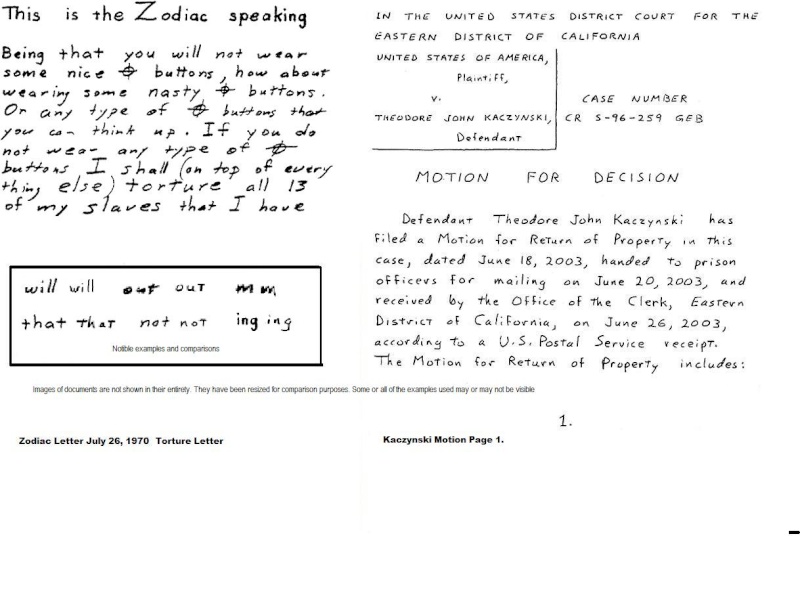

Rules him out, imo…no curvy ‘f’, different ‘+’ symbols, too. Not the handwriting of Zodiac, imo.

QT

*ZODIACHRONOLOGY*

Rules him out, imo…no curvy ‘f’, different ‘+’ symbols, too. Not the handwriting of Zodiac, imo.

QT

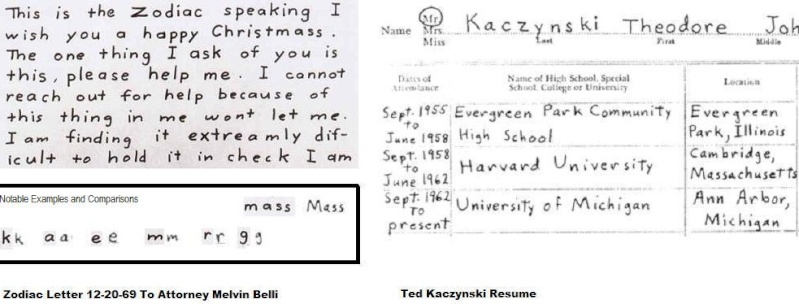

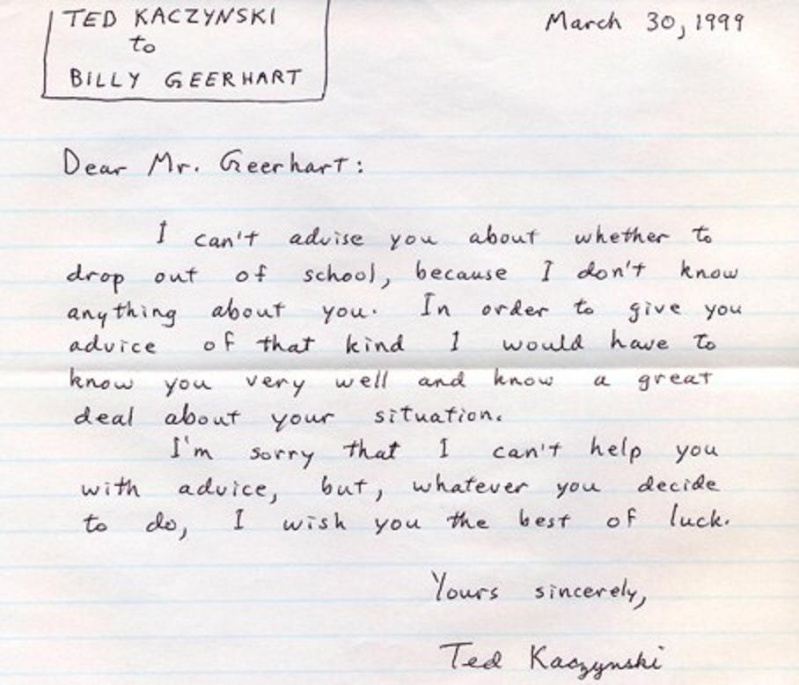

The first thing I noticed about both the Zodiac Killer’s writing and Ted Kaczynski’s writing is the number of different handwriting styles they both had. I personally only use one, ever. I would be hard pressed to write in cursive. Yet, Ted is writing journal after journal in cursive writing and then letter after letter in print. As well as in a very complicated number code, which uses a different handwriting style all together, (and also typing). It’s as if he has different personalities and you can tell who’s talking by the handwriting.

This is also true for all of the EAR/ONS documents as well. ONS used four different handwriting styles. They are so different that there was some speculation that two people had written them. In the Custer paper, ONS uses both script and print and, in his punishment paper he has two completely different handwriting styles, yet they appear to be from the same person.

I’m not ruling anyone out based on handwriting samples. None of these criminals had just one style of handwriting.

Not sure I have seen that before. Thanks for posting it DJ.

QT you are comparing print to cursive. Not a reliable thing to do. Regarding cursive it’s actually not a bad example. Z gave us a small sample of cursive on the SLA card and at a quick glance 2 out of the 3 characters are quite similar to Ted’s in this letter. Those would be the S and and the A, the l though in Ted’s writing seems to be tight and pointed sometimes barely displaying the gap in the loop. Z’s example is rather more open and rounded.

That’s my thought’s on it anyway.

Rules him out, imo…no curvy ‘f’, different ‘+’ symbols, too. Not the handwriting of Zodiac, imo.

QT

I agree with Darla and Trav. Above all you cannot compare cursive to print. Ted’s print writing is very Z like, including checkmark r’s, three stroke k’s, five stroke m’s, low cross t’s, overall feel and spacing, and several other matches, not even considering that Z may have disguised some writing.

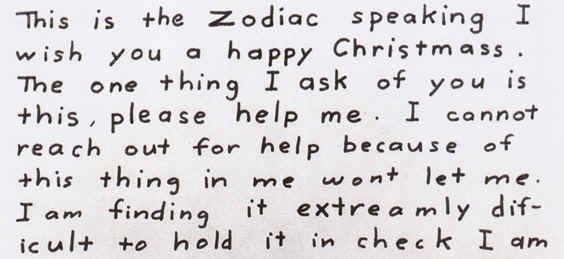

These samples and comps below should show that TK and Z have very similar handwriting. Several people with little interest in TK as a suspect have told me that the handwriting is the closest match among the major named suspects. Take a look and decide for yourself.

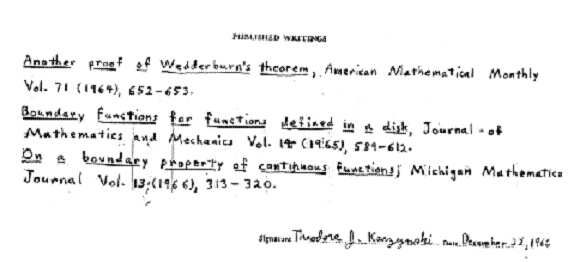

Zodiac often but not always did a 3 stroke "k", Kaczynski often but not always did a 3 stroke "k". Zodiac often did a 5 stroke "m", same as Ted. Other matches include the checkmark "r", short caps and bottom on the capital "I" and frequent cursive looped back on the "d". Look at Ted’s "k" in "Park" – a clear 3 stroke. Morrill said few people in the general population do 3 stroke "k" or 5 stroke "m" so those would be things he would look for. I also blew up the Ted letter to the boy.

GRAPHICS AND RESEARCH BY AK WILKS AND AWESHUCKS – A HANDWRITING COMPARISON – ZODIAC AND KACZYNSKI

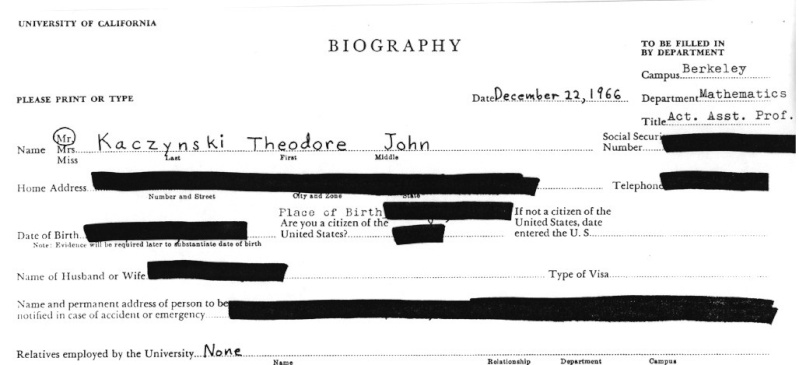

From Doug Oswell, the Application Bio by Kaczynski to the U Cal Berkeley, December 1966.

The writing looks particularly Zodiac like to me, compare it to the Belli letter.

TAHOE 27: You have always provided nice comparisons AK!

Ted’s writing has always been closest to Zodiac’s than most others, imo.

Since I don’t believe Zodiac responsible for all the crimes or letters, many of these guys still remain intriguing. If Zodiac wasn’t responsible for some, who were the ones who were?

MODERATOR