I’m pretty sure that A&E broadcast a portion of the EAR/ONS DNA profile. Here’s what I picked up from the shows posted on the internet.

www.youtube.com/watch?v=3Ih-GKZAnuc

6:15 of 7:40

4:11 of 7:40

6:15 of 7:40 6:44 of 7:40

Robert Stack says at 6:44 "….making the man who owns THIS genetic profile one of the biggest serial offenders…"

www.youtube.com/watch?v=6TfaY6FwXx8

There is more at .26 of 9.57 which gives us the position of the X and the Y. The X are the numbers on top, the Y the numbers on bottom.

IMO this is a partial DNA Fingerprint for ONS.

X Y

13 14

28

34.2

17

16 18

22 23

At 5.53 of 9.57 they give us some of the Code

Locus 1 =D3S1358

TI T2

15 16

Locus 2=vWA

14 15

Locus3=FGA

21

I am no major serial killer researcher, but isn’t the progression of most serial killers, or criminals in general geared toward being more up close and personal over time? Why would TK get more remote and impersonal if he was Z or any other killer? That is, if what I am saying is correct about most criminals in general…

Here is the back of the EAR map page. Its blurry because it was screen captured from a news show. The cropped version that was released to the public by LE through LA Magazine is also attached.

Here is Ted K.’s cursive handwriting. It looks similar to the word Milling. I’m sure someone else could do a better job of comparing the two samples. Notice in the top right hand corner of the LA Magazine image there is a reverse "Z " symbol under the name Melanie (which has been crossed out.). AK just pointed out that Ted signed his name with the "Z" under it.

That is excellent work Darla, thanks.

I know one element, the DQAlpha, of the EAR/ONS DNA. With these other elements you found I could more definitively rule someone in or out.

That does look like a large Z similar to what Ted writes underneath his name.

I see some similarities and differences in the writing. the problem with cursive is it is hard to compare, as most cursive writing all looks similar. Have to look at this further. I do see an interesting similarity between the lower case "g" in "milling" and the lower case "g" in "Chicago".

MODERATOR

And again a VOLKSWAGEN is the car of chioce for this perp.

CONCLUSIONS

The EAR is a WMA in his late teens or early twenties. He is about 5’8" in height with a pale skin, light colored eyes (blue or hazel) moderately long, dark blond or light brown hair and a slender build. He most probably drives an older VW of a nondescript color, sighted under varying lighting conditions and reported variously as dark green, gray or silver blue. It may have expanded rear fenders and wide wheels. He has the tendency to return to areas he appears to have familiarized himself with. These areas seemingly can be distinguished by homes up for sale and escape routes where he can avoid detection during the early morning hours.

Yes in the Bates, Zodiac, EAR/ONS and other possibly related unsolved CA murders, we see VW’s occurring as both victim vehicles and as a suspect vehicle.

MODERATOR

Beware, lest another urban myth is born!

VW’s were (and are) everywhere.

Wiki (I believe every word) reminds us that "By 2002, over 21 million Type 1s had been produced, but by 2003, annual production had dropped to 30,000 from a peak of 1.3 million in 1971."

It would be much more strange if there were NO mention of VW’s in these cases….. (Two cents.)

Don’t mind me btw, do carry on.

Beware, lest another urban myth is born!

VW’s were (and are) everywhere.

Wiki (I believe every word) reminds us that "By 2002, over 21 million Type 1s had been produced, but by 2003, annual production had dropped to 30,000 from a peak of 1.3 million in 1971."

It would be much more strange if there were NO mention of VW’s in these cases….. (Two cents.)

Don’t mind me btw, do carry on.

Valid point.

I think it is worth noting how VW’s seem to crop up as both victim and suspect cars in Bates, Zodiac, EAR/ONS and other unsolved California murders. It could mean something.

But as you note VW’s were very popular in the 60’s and 70’s, so maybe it is not unusual.

I never understood how a car initially designed and supported by Hitler became so popular among hippies, the counterculture and college students. Maybe just because it was a good cheap, reliable, high gas mileage car with an added cool factor of being foreign. Who knows? But it is true they were very popular.

MODERATOR

Beware, lest another urban myth is born!

VW’s were (and are) everywhere.

Wiki (I believe every word) reminds us that "By 2002, over 21 million Type 1s had been produced, but by 2003, annual production had dropped to 30,000 from a peak of 1.3 million in 1971."

It would be much more strange if there were NO mention of VW’s in these cases….. (Two cents.)

Don’t mind me btw, do carry on.Valid point.

I think it is worth noting how VW’s seem to crop up as both victim and suspect cars in Bates, Zodiac, EAR/ONS and other unsolved California murders. It could mean something.

But as you note VW’s were very popular in the 60’s and 70’s, so maybe it is not unusual.

I never understood how a car initially designed and supported by Hitler became so popular among hippies, the counterculture and college students. Maybe just because it was a good cheap, reliable, high gas mileage car with an added cool factor of being foreign. Who knows? But it is true they were very popular.

The reason for their popularity is because the were affordable and outside the box. Nothing like them had been designed at the time.

Look at it like this…a Prius, or insert any hybrid car, in today’s world, is the equivalent. They were different and eye catching. Maybe not in a luxury or sports car kind of way, but people in those days wanted individuality. While this gave it to them they did not realize they were just one of the masses.

If a under middle class citizen can afford something that doesn’t look run of the mill, they will buy it. Simply because it sets them apart from others in their class solely based on looks.

To prove my case, name another car that looked like a VW at anytime in production and cost as little.

Hell…my dad is a doctor and he even had one when they came out.

Wonder how many young American boys in the mid 60s would know to go to the "trunk" to disable a VW beetle.

Wonder how many young American boys in the mid 60s would know to go to the "trunk" to disable a VW beetle.

My guess would be about as many as knew how to disable a car engine in general. It’s an engine…happens to be on the other end of the car.

Here is the psychological profile of Kaczynski.

Psychological Evaluation of Theodore Kaczynski

[This report can also be found elsewhere on the Internet, and is provided here in a reader-friendly layout to facilitate study; original typing errors and omissions have been retained.]

Dr. Sally C. Johnson’s psychological report describes Theodore Kaczynski, the confessed Unabomber, as a man whose early brilliance was ruined by paranoid schizophrenia.

Johnson made her evaluation after interviewing Kaczynski, his family and people who knew him, analyzing psychological tests, and studing of the Unabomber’s journals which document over 40 years of his life.

She cites "an almost total absence of interpersonal relationships," and "delusional thinking involving being controlled by modern technology" as examples of his illness.

Kaczynski increasingly withdrew from society as he grew older, and his journals reflect a feeling of social alienation, suspicion and anger he found hard to express. The report says one of his motives for writing the journals was that he intended to kill people and did not want society to think he was mentally ill.

The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco ruled that the psychiatric report should be made public in order to provide a better understanding of the Unabomber’s motivations.

FORENSIC EVALUATION NAME:KACZYNSKI, Theodore John

DOCKET NUMBER:CR S-96-259 GEB

DATE OF BIRTH:05/22/42

DATE OF REPORT:01/16/98

IDENTIFYING INFORMATION: Theodore John Kaczynski is a 55 year old white single male, currently housed in pretrial status at the Sacramento County Jail in Sacramento, California. He was most recently residing in Lincoln, Montana. On 01/09/97, the Honorable Garland D. Burrell, Jr., United States District Court Judge for the Eastern District of California, issued an order that Mr. Kaczynski be examined by Bureau of Prisons physicians and others authorized by such physicians to assist in the study and examination to determine his mental competency to stand trial. The Order further indicated that the examining physicians are authorized to access all pertinent medical and collateral information, including psychiatric and medical records, and psychological testing. The examination was ordered to commence on 01/12/98. On 01/12/98, Judge Burrell issued a supplemental Order for Dr. Sally Johnson to travel to Sacramento to conduct the examination of the defendant at the Sacramento County Jail. The Order outlined that Dr. Johnson should prepare a report of the examination of the defendant pursuant to the Provision of 18, U.S. Code, Sections 4247(b) and (c). The examination should include: the defendant’s history and present syndromes; a description of the tests employed and the results; the examiner’s findings; and the examiner’s opinions as to diagnosis, Prognosis, and whether the defendant is suffering from a mental disease or defect rendering him mentally incompetent to the extent that he is unable to understand the nature and consequences of the Proceedings against him or to assist properly in his own defense. Copies of the report were ordered to be provided to the Court, counsel for the defendant, and the Government by 7:OOPM on Ol/16/98. on 01/13/98, Judge Burrell issued an additional Order which directed that trial counsel for the defendant were to provide Dr. Johnson with copies of each of the letters admitted to the Court – under seal by the defendant and all of the transcripts of ex parte and in camera hearings. If these materials were included in the competency report, that aspect of the report would not immediately be given to the Government. Rather, the Government would be provided the opportunity to petition the Court for access excluded materials at a later date. The trial judge and the defendant’s counsel would be given a copy of the competency report in its entirety. In accordance with these Orders, the psychiatric evaluation was conducted between 01/12/98 and 01/16/98.

In the indictment filed 06/18/96, Mr. Kaczynski was charged with violations of 18, U.S. Code, Section 844(d), Transportation of an Explosive with Intent to Kill or Injure (four counts); 18, U.S. Code, Section 1716 Mailing an Explosive Device in an Attempt to Kill or Injure (three counts); and 18, U.S. Code, Section 1924(c)(1), Use of a Destructive Device in Relation to a Crime of Violence (three counts). These charges involved use of an explosive device to kill Hugh Scrutton on or about 12/11/85; the use of an explosive device that injured Dr. Charles Epstein on or about 06/22/93; the use of an explosive device to injure Dr. David Gelernter on or about 06/24/93; and the use of an explosive device to kill Gilbert B. Murray on or about 04/24/95. Mr. Kaczynski is represented by Federal Defenders Quinn Denvir, Judy Clarke, and Gary Soward. Special Attorneys to the U.S. Attorney General assigned to this case are Robert J. Cleary, Stephen P. Freccero, R. Steven Lapham, Bernard F. Hubley, and J. Douglas Wilson.

Extensive collateral information was available for review and use during this evaluation period. This included copies of Judge Burrell’s Court Orders dated 01/09/98, 01/12/98, and 01/13/98; the indictment filed on 06/18/96; extensive information in regard to the charged offenses; medical records on Mr. Kaczynski, including a copy of his birth certificate from the State of Illinois; dental records from William Schauer, MS, and Thomas Ditchey, MS, through 1982; University Health Service records from Harvard University beginning in September 1958; hospital summary from Billings Hospital in Chicago, Illinois for hospitalization from 09/10/59 to 09/15/59; records from Dr. Walter Peschel in Missoula, Montana; records and correspondence from Carolyn C. Goren, M.D., April 1991 through January 1995; records from St. Peters Community Hospital in Helena, Montana; records from Glen Wielenga, M.D., of Lincoln, Montana for time periods between 1991 and 1993; records from the Sacramento County Jail for the time period between 1996 and 1998; and records from the Health Services Department at the Federal Correctional Institution (FCI) Dublin, California, for a period of detention from 09/03/97 to 11/06/97.

Collateral information provided by the prosecution included copies of the Government trial brief filed under seal; selected statements and writings by the defendant; a letter outlining the Proof of Uncharged Crimes dated 07/29/96 addressed to Quin Denvir, Federal Defender; statements concerning the charged bombs, information on disguises and aliases, and targeting of victims; a copy of Mr. Kaczynski’s original autobiography (1979); the Unabomb correspondence and manifesto; declarations from Park Elliott Dietz, M.D., M.P.H., Ph.D., dated 10/02/97, and Phillip J. Resnick, M.D., dated 10/02/97; and an Analysis of Neuropsychological Testing on Theodore Kaczynski by John T. Kenny, Ph.D., dated 12/29/97.

Collateral information provided by the defense included a chronology of charged and uncharged offenses; transcripts of court proceedings in United States vs. Theodore Kaczynski dated 11/21/95, 01/05/98, 01/07/98, and 01/08/98; Declarations of defense retained experts including David Foster, M.D., dated 11/11/97 and 11/17/97, Xavier Amador, Ph.D., dated 11/16/97; Karen Froming, Ph.D., dated 11/17/97; a letter to Elizabeth Gilbertson, M.D., from Theodore Kaczynski; the autobiography of Theodore Kaczynski prepared in accordance with participation in the Multiform Assessment of College Men Study, by Henry A. Murray at Harvard University; a typewritten transcript of Theodore Kaczynski; autobiographical notes 1979; a social history chronology of Mr. Kaczynski; and excerpts from correspondence between 1975 and 1991 and journals between 1957 and 1971. Also provided was a copy of the Refutation (a 15 chapter manuscript written by Mr. Kaczynski primarily between August and November 1997). Pursuant to a Court Order dated 11/13/97, the examiner was provided copies of the letters written by Mr. Kaczynski to Judge Garland D. Burrell, Jr., dated 12/18/97 and 01/05/98, and copies of the sealed reporter draft transcripts dated 12/18/97, 12/19/97, 01/05/98 and 01/07/98 (in camera proceedings).

The examiner also reviewed the complete set of writings obtained from Mr. Kaczynski’s cabin in Montana. This included a series of journals spanning the time period of 1960 to present; extensive correspondence by Mr. Kaczynski and to Mr. Kaczynski; and detailed records of scientific experiments conducted by Mr. Kaczynski. In addition of review of the extensive collateral information, the examiner also had the opportunity to visit Mr. Kaczynski’s cabin at the storage site outside of Sacramento and to review extensive photographs of the cabin contents.

Initial interviews were conducted with defense attorneys Quin Denvir, Judy Clarke and Gary Soward, and prosecuting attorneys Robert Cleary and Stephen Freccero on 01/11/98. Prosecuting attorneys were then interviewed separately on 01/11/98. Defense attorneys were interviewed on 01/12/98. Additional interviews with both defense and prosecuting attorneys took place throughout the week, in regard to obtaining necessary information and managing the logistics of the evaluation process. Personal interviews were conducted with Wanda Kaczynski, mother of the defendant, and David Kaczynski, brother of the defendant, on 01/13/98. Phone interviews were conducted with defense retained experts David Poster, M.D., Raquel Gur, M.D.,Ph.D., Ruben Gur, Ph.D., and Karen Froming, Ph.D.; and prosecution retained experts Park Dietz, M.D., and Phillip Resnick, M.D. A phone interview was also conducted with Sherry Woods, librarian in Lincoln, Montana.

DATES OF CONTACT/PROCEDURES ADMINISTERED: During this evaluation, Mr. Kaczynski was interviewed by Sally C. Johnson, Chief Psychiatrist and Associate Warden of Health Services for the Federal Correctional Institution in Butner, North Carolina. During this evaluation, Mr. Kaczynski was interviewed by the examiner on eight occasions at the Sacramento County Jail, with a total interview time Of approximately 22 hours. The interviews took place either in the line up room conference area or in confidential attorney visiting booths on the second or eighthfloor. At the start of the initial interview and briefly during subsequent interviews on 01/12/98 and 01/13/98, the defense attorneys were present to answer Mr. Kaczynski’s questions regarding the evaluation process. In addition to the clinical interviews, formal review was conducted of previous medical evaluations, as well as previous neuropsychological and psychological testing results. Additional psychological testing administered during this evaluation included the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 (01/12/98), the Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory-II (01/12/98), the Beck Depression Inventory (01/15/98), and the Draw a Person Picking an Apple from a Tree projective drawing (01/15/98). Psychological testing administered during this evaluation was administered by Dr. Johnson. Scoring and interpretation of tests were accomplished with the assistance of psychology staff at FCI Butner.

At the outset of this evaluation and repeatedly throughout the week, the purpose of the evaluation and limits of confidentiality of information provided were discussed with Mr. Kaczynski. He was informed that the information and the observations made would provide the basis for completion of a report which would be available to the Judge, as well as the Defense and Prosecuting Attorneys. He was advised that a provision was in place to protect the privacy of any en camera materials. He demonstrated an adequate understanding of this information.

BACKGROUND INFORMATION: The information outlined in this section is a composite of that obtained through interviews with Mr. Kaczynski, review of the extensive collateral information, and interviews with those individuals outlined above. Mr. Kaczynski was viewed as a relatively reliable historian in regard to most of the information that was provided. On advice of his attorneys, he provided only limited information regarding his activities immediately around the time of the currently charged offenses. Mr. Kaczynski tended to emphasize or minimize certain aspects of his history and recited descriptions of many events by rote, using the wording used in his writings. With encouragement, he was able to provide additional detail regarding some of those points. The information provided by Mr. Kaczynski was generally consistent with that provided by other sources.

Theodore John Kaczynski was born in Chicago, Illinois on 05/22/42. He is the oldest son born to Theodore Richard Kaczynski and Teresa (Wanda) Dombeck Kaczynski. He has one brother, David Kaczynski, who is sevens years younger, born in 1949. His father is deceased, having died on 10/02/90 from a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head. His father had been diagnosed shortly before his death with lung cancer with metastasis to the spine. His mother is 80 years old and resides in Schenectady, New York, near David and his wife Linda.

Mr. Kaczynski’s father was initially employed as a sausage maker over the years. He spent part of his employment working for relatives in that business, but subsequently obtained employment with a food products company and then with several foam cutting companies in the Chicago area. He transferred with the latter job to Iowa and then back to Illinois. He reportedly provided adequately for the family, from a financial standpoint. He had no clear history of psychiatric illness, although it is noted that he committed suicide reportedly in response to his poor prognosis and significant pain related to the diagnosis of cancer. He had no criminal or substance abuse history. Wanda Kaczynski has spent most of her life working in the home, although earlier she completed approximately two years of college education. At a later point, when the family moved to Iowa, she completed her degree in teaching, and subsequently taught for a few years. Most recently, she was employed in an office situation She has no history of mental illness, [text redacted]

Available reports indicate that the pregnancy with Mr. Kaczynski was full term with no significant problems prior to delivery. As a young child, he reached developmental milestones such as sitting up, walking, and talking within normal parameters. He was hospitalized at the age of approximately nine months, for several days, as the result of an allergic reaction. Hospital course was apparently uneventful and he was discharged without known medical sequelae. Conflicting reports exist as to the significance of that hospitalization. Records reviewed through notes kept in Mr. Kaczynski’s baby book do not provide much information in regard to problems following that hospitalization. Information provided by Wanda Kaczynski, however, indicates her perception that his hospitalization was a significant and traumatic event for her son, in that he experienced a separation from his mother (due to routine hospital practices). She describes him as having changed after the hospitalization in that he was withdrawn, less responsive, and more fearful of separation from her after that point in time. Mr. Kaczynski experienced usual childhood diseases including mumps and chicken pox, and underwent a tonsillectomy at age six and removal of a congenital cyst of his upper jaw at age 12 or 13.

Again somewhat conflicting accounts exist as to his early social development. He was viewed as a bright child and was described by his mother as not being particularly comfortable around other children and displaying fears of people and buildings. She noted that he played beside other children rather than with them. Her concern about him apparently led her to consider enrolling him in a study being conducted by Bruno Betleheim regarding autistic children. No detailed information is available about this, but Wanda Kaczynski indicated that she did not pursue that opportunity. Instead, she utilized advice published by Dr. Spock in attempting to rear her son.

Mr. Kaczynski describes his early childhood as relatively uneventful, until the age of eight or nine. He described memories of early play with other children, although he too recounts being somewhat fearful of people and describes himself as socially reserved. He recounts a few significant episodes in his early life referencing the hospitalization mentioned above, being scalded by boiling water, and falling and cutting his tongue. Mr. Kaczynski denies any history of physical abuse in his family. He does admit to receiving occasional spankings, but felt that this was not excessive or cruel. He does specifically describe extreme verbal and emotional abuse during his upbringing, although he did not identify this as a problem until he was in his 20s.

The family initially lived in a working class neighborhood in Chicago and Mr. Kaczynski described the family as having middle class aspirations but living only one step above the slums. He remembers his mother focusing on his dialect, encouraging him not to talk like the kids in the street, and responds that he complied by speaking one way at home and another way when interacting with the other children.

By the age of eight or nine, Mr. Kaczynski describes that he was no longer well accepted by the neighborhood children or his peers at school. The neighborhood children "bordered on delinquency" by his account, and he was not willing or interested in being involved in their activities. The family moved several times, bettering their housing status, eventually moving to Evergreen Park, Illinois, when he was approximately age 10. He describes this as a middle class suburb of Chicago.

Mr. Kaczynski attended kindergarten and grades one through four at Sherman Elementary school in Chicago. He attended fifth through eighth grade at Evergreen Park Central school. As the result of testing conducted in the fifth grade, it was determined that he could skip the sixth grade and enroll with the seventh grade class. According to various accounts, testing showed him to have a high IQ and, by his account, his parents were told he was a genius. He claims that his IQ was in the 160 to 170 range. Testing supposedly conducted at that time has not been made available for review. Mr. Kaczynski described this skipping a grade as a pivotal event in his life. He remembers not fitting in with the older children and being the subject of considerable verbal abuse and teasing from them. He did not describe having any close friends during that period of time.

He attended high school at Evergreen Park Community High School. He did well overall from an academic standpoint but reports some difficulty with math in his sophomore year. He was subsequently placed in a more advanced math class and mastered the material, then skipped the 11th grade. As the result, he completed his high school education two years early, although this did require him to take a summer school course in English. During the latter years of high school he was encouraged to apply to Harvard, and was subsequently accepted as a student, beginning in the fall of 1958. He was 16 years old at the time.

Mr. Kaczynski completed his undergraduate degree in Mathematics, graduating in June 1962, at the age of 20. He began his first year of graduate study at the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor in the fall of 1962. He completed his Masters and Ph.D., by the age of 2 5 . Following graduation, he accepted a position as assistant professor in the Math Department at the University of California at Berkeley, and remained in that position from September 1967 until June 1969.

During his high school years, Mr. Kaczynski was not involved in many activities. He did play the trombone and speaks with pride about the lessons he took from a well known trombone instructor. He denies any involvement in sports or interest in group activities. After starting college, he was hospitalized briefly and diagnosed as suffering from infectious mononucleosis. He recovered without significant sequelae.

Mr. Kaczynski describes being happy with the birth of his younger brother, and he and family report a relatively strong relationship between the boys (when age differences were taken into consideration), throughout Mr. Kaczynski’s school years.

Mr. Kaczynski’s employment history is somewhat limited and consists of a variety of jobs held for relatively short periods. In the summer before college, he was involved in part time activities in maintenance and repair at a local elementary school. The summer after his freshman year of college, he worked at a spice packing plant. During graduate school in Michigan, he worked as a teaching fellow for approximately three of the five years. As noted, he then accepted an assistant professor position in the Math Department at Berkeley. Following resignation from that position, he returned to live with his parents in Lombard, Illinois, and began looking for land, where he could establish a more isolated existence. In 1969 he had some temporary employment at warehouse jobs and factories while looking for the land. From 1971 until the time of his arrest, he was for the most part unemployed and living off the land, with some limited financial support from his family. Intermittently, he worked to obtain needed money, which included employment in the fall of 1972 and spring of 1973 in masonry and groundskeeping jobs. In 1978 and 1979, he worked a few months at a foam cutting company in Lombard, Illinois, where his father and brother were employed. He was fired from that job after inappropriate behavior towards the female manager and subsequently worked briefly at the Prince Castle Restaurant & Equipment Company.

Mr. Kaczynski had no periods of service in the military and indicated he was deferred from the draft due to his status as a student and later as a teacher.

Prior to his current legal situation, Mr. Kaczynski has had no significant criminal record of arrests or incarceration. He did receive a traffic ticket for passing a stopped school bus about 25 years ago. This required him to appear at the Justice of the Peace Court to resolve the ticket. No attorney representation was involved, he pled guilty, and paid a fine of $30. He has never retained an attorney for any other reasons. He has never served as a juror nor been a plaintiff in a legal action.

Mr. Kaczynski denies any significant history of substance use or abuse, including alcohol or nicotine. This is confirmed by other sources of collateral information.

Mr. Kaczynski describes no religious affiliation [text redacted]. Since living on his own, he has not affiliated with any religion.

[text redacted]

Mr. Kaczynski has no history of inpatient psychiatric hospitalizations or ongoing treatment. He does have a history of brief contacts with mental health systems in various places. Although he had interactions with guidance counselors around academic issues in junior high and high school, it appears he was not involved in any type of counseling. As referenced earlier, he underwent a battery of psychological testing in the fifth grade, the results of which initiated the decision for him to be advanced academically ahead of his peer group. After entering Harvard, he voluntarily became involved a psychological study of young men. He underwent some psychological testing and completed a written autobiography at that time. Results from that study will be discussed in the psychological testing portion of this report.

While at the University of Michigan he sought psychiatric contact on one occasion at the start of his fifth year of study. As referenced above, he had been experiencing several weeks of intense and persistent sexual excitement involving fantasies of being a female. During that time period he became convinced that he should undergo sex change surgery. He recounts that he was aware that this would require a psychiatric referral, and he set up an appointment at the Health Center at the University to discuss this issue. He describes that while waiting in the waiting room, he became anxious and humiliated over the prospect of talking about this to the doctor. When he was actually seen, he did not discuss these concerns, but rather claimed he was feeling some depression and anxiety over the possibility that the deferment status would be dropped for students and teachers, and that he would face the possibility of being drafted into the military. He indicates that the psychiatrist viewed his anxiety and depression as not atypical. Mr. Kaczynski describes leaving the office and feeling rage, shame, and humiliation over this attempt to seek evaluation. He references this as significant turning point in his life.

Beginning in the spring of 1988, Mr. Kaczynski made several contacts with mental health systems around the issue of establishing relationships with women. He indicates that in 1988 he was suffering from insomnia and a renewed interest in getting advice and moral support to establish a relationship with a woman. He describes picking a psychologist’s name out of the phone book and writing her a letter about his interest. He indicates that his decision to seek this type of counseling resulted after having a dream about a young woman. Upon awakening he had the idea that perhaps at age 45 it was not too late for him to establish a relationship, and at that point he thought of leaving his isolated life in Montana and finding a job and a female for himself. As noted, he sent a detailed letter to the therapist and saw her once. He had a positive experience in the session and subsequently sought employment. He states that during the session the therapist, Elizabeth Gilbertson, had mentioned the thought of her arranging a meeting with him and some of her female clients. He subsequently wrote her a letter with the hopes of reminding her to do so, but she did not pick up on his implied message. He also came to the realization that he could not afford to see her regularly, although he could have afforded one more visit. Subsequent to that session, he wrote to the Mental Health Center in Helena, requesting that he be assigned a therapist or counselor with whom he could correspond by mail. Mr. Kaczynski indicates that this could not be worked out and he remained depressed for the next several months. Although the depression lightened eventually, it remained there to some degree until 1994.

In 1991 Mr. Kaczynski contacted a local general practitioner, Dr. Glen Wielenga, in Lincoln, concerning insomnia. Mr. Kaczynski indicates the doctor suspected he was depressed, but he was somewhat dissatisfied with Dr. Wielenga’s assessment. Dr. Wielenga did prescribe Trazadone at a dose of 50mg. at bedtime. Mr. Kaczynski took it for three days. It made him sleep, but he experienced daytime drowsiness and gas from it, and discontinued the medication. He subsequently wrote to the Mental Health Center in Great Falls, asking for recommendation of a few people he could contact in regard to finding a psychiatrist, but did not follow through and his insomnia remitted without treatment.

Records indicate that Mr. Kaczynski saw Dr. Gilbertson as noted above. He also made contact via letter to Dr. Melnick, a psychiatrist in Missouri . He was subsequently unable to afford her fees.

Around this same time, in the spring of 1991, he set up an appointment with Carolyn Goren, M.D., in Missoula, Montana. He sought evaluation and treatment for symptoms of palpitations and stress. Prior to his visit, he sent Dr. Goren a letter outlining his concerns. He was seen on 04/29/91, and subsequently had one follow up visit some months later. After his initial visit, Mr. Kaczynski continued to monitor his blood pressure, which remained within normal limits, and provided these values to Dr. Goren on a semi annual basis for several years. No significant cardiac problems were identified during his evaluation time. Collateral information also supports that Mr. Kaczynski sent a letter to the Director of the Golden Triangle Community Mental Health Center in October 1993 concerning his problem of insomnia and asking for location of a suitable psychiatrist that he could see on a reduced fee. There was no follow through with an appointment. Mr. Kaczynski had no other mental health contacts prior to the period after his arrest on the current charges. [text redacted].

Following his visit to Dr. Goren and his belief that perhaps the potential of an ongoing relationship existed with her, he made the decision to acquire a more conventional career. He decided to attend school at the undergraduate level to obtain a degree in journalism. He corresponded with the University of Montana and subsequently was required to take the Graduate Record Exam. Even after he determined that there was not a possibility of an actual relationship with Dr. Goren, he took the exam anyway and reportedly scored quite well. He never matriculated to the University.

In reviewing available background information on Mr. Kaczynski’s life, it was useful to review his two lengthy autobiographical documents. At the time he went to Harvard and became involved in a psychological study of students there, he was asked to write the first autobiography. He completed this in one or two days, in 1959. Twenty years later, over a period of several months, he wrote a 216 page autobiography of his life.

In the autobiography in 1959, Mr. Kaczynski describes an uneventful early childhood, and indicates that he was somewhat rebellious towards his parents, who were quite lenient with him. He describes his relationship with his parents as quite affectionate and denies any involvement in delinquent behavior. He notes the testing that occurred in fifth grade and the impact on his life of skimping the sixth grade. Despite that, he claims that he did establish a few friendships in junior high. [text redacted]. In addition to playing the trombone in the school band for a few years, he also collected coins. He denies any dating during junior high or high school. Upon entering Harvard, he was struck with the realization that he was no longer smarter than all the other students. Nonetheless, he did above average work, excelling in math. Later, he notes that during the last few years, his relationship with his parents had deteriorated and often resulted in arguments. He describes his mother as having an "artist’s temperament" and indicates he respected her more than his father. He describes his father as an extrovert, who had a number of community interests. At the end of the autobiography, he lists a variety of information that he "forgot to include." Of note, he references quarreling a lot with his brother, but generally having a friendly relationship, although he viewed himself as being superior in intellect and in strength of will. He noted he enjoyed building structures out of wooden blocks and playing with his chemistry set. He references one friend, whom he describes as a "rather dull fellow with average intelligence and not too interesting." He viewed himself as being collectively regarded as a shy, hard working student.

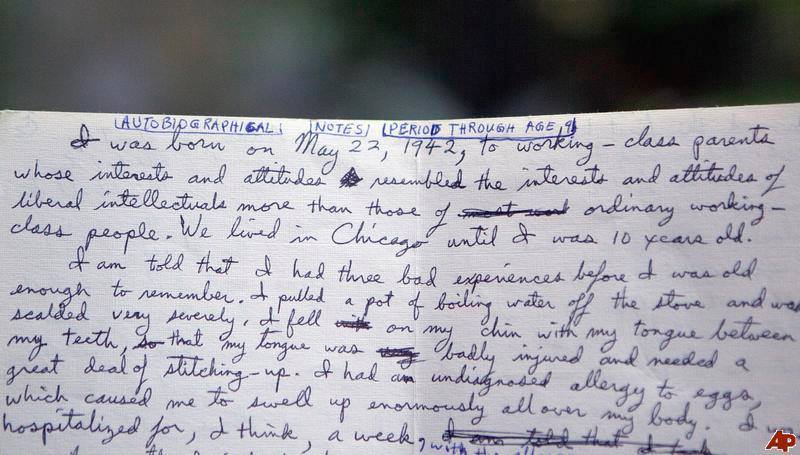

The autobiographical notes completed in 1979 provided a much more detailed account of Mr. Kaczynski’s view of his history. This is divided into various age periods and separated into the periods zero through age nine; age 10 to 15; age 16 to 20; age 20 to 24; age 24 to 27; and then from age 27 on (to age 37). The original copy is handwritten.

It is of note that after leaving his job at the University of California at Berkeley, Mr. Kaczynski spent approximately two years attempting to locate a piece of wilderness land upon which he could live, isolated from society. In 1971 he succeeded in building a small cabin on a piece of land that he purchased in conjunction with his brother, in Lincoln, Montana. From 1971 until his arrest on 04/03/96, Mr. Kaczynski’s primary residence was HCR 30, Box 27, Lincoln, Montana 59630. The cabin was situated a short distance off a road, but the approximately one and one-half acre of land provided him solitude and ready access to wilderness area. Although he had neighbors in the vicinity, he was able to maintain minimal contact with them if he so chose. During that time period, he made an effort to live off the land and over a period of years, developed increased sophistication with identification of edible plants, gardening, food preservation, hunting, and game preservation, and developed some necessary skills in the area of tool making and sewing. The cabin was not equipped with any plumbing and his water supply was provided by a creek located near the cabin. He did not have any electricity at the house although hook up was available nearby. During the early years of his residence there, he had a car and subsequently for a short time a pick up truck. After that, he maintained a bicycle for transportation or walked into town, where he had access to public transportation. The cabin was located approximately four miles outside of Lincoln. Mr. Kaczynski remained there, except for several short periods where he traveled and sought employment to earn some money. He was provided with a minimal stipend from his parents throughout this time period and used the money he had originally earned at Berkeley and other intermittent jobs to support himself – He estimated that it generally cost him less that $400 a year to live, after he became established in his routine.

In June 1969, after leaving his job a Berkeley, Mr. Kaczynski moved to Lombard, Illinois to stay with his parents. That summer he and David traveled to Canada, looking for a piece of wilderness land for Mr. Kaczynski to buy. He applied for permission to purchase land in British Columbia. During that time, David was enrolled at Columbia University. Following his graduation in 1970, David moved to Great Falls, Montana. Throughout the summer of 1970, Mr. Kaczynski continued to look for wilderness land in Alaska and subsequently learned that his application for land in Canada was denied. He had a short period of employment for a few months at the end of 1970 with Abbot Consultants in Elmherst, Illinois. In the summer of 1971 he purchased his land in Lincoln, where he built his cabin with minimal assistance from his brother. During the period of late 1972 until December 1973, Mr. Kaczynski worked at a variety of jobs in Chicago and Salt Lake City, Utah. He returned to his cabin in Montana in June 1973. In September 1974, for two to three weeks, he worked at a gas station in Montana, earning a few hundred dollars. In January 1975 he traveled to Oakland, California, and returned to his cabin in March. In May 1978 he returned to Chicago in search of work and obtained employment at Foam Cutting Engineers, where his father and brother were employed. He continued in that job for about a month, until he was fired. He was subsequently employed by Prince Castle from September 1978 until March 1979. After quitting his job at Prince Castle, he lived with his parents in Lombard, Illinois and in the early summer of 1979 returned to his cabin in Montana. He remained there until mid 1980, when he traveled to Canada, again in search of wilderness land. Upon his return and with his lack of success in finding wilderness, he settled into his cabin where he remained in residence until the time of this arrest on the current charges.

While residing in his cabin, he would regularly travel to town for supplies, go to the Post Office, and use the Library. Periodically he would travel beyond Lincoln. This was usually accomplished by bus.

Sometime in the 1980s, Mr. Kaczynski decided to study Spanish. He claims he acquired an old Berlitz Spanish instruction book for a few dollars and used that as the basis for his studies. His writings show that he practiced his Spanish by doing translations and corresponded with an Hispanic, [text redacted] to assist in practicing the language. Review of information from his cabin shows that he also translated material that he viewed to be more sensitive into Spanish in his journals.

Over the time period from 1969 until his arrest, Mr. Kaczynski recorded many of his thoughts, ideas, and activities in writing and maintained these writings in his cabin. He also maintained correspondence with his family over a number of years and saved much of that correspondence. Review of these extensive writings provides a narrative and his own analysis of his life and behaviors.

The following information is a composite of that obtained through review of the extensive writings completed by Mr. Kaczynski. Throughout his writings and conversations, he focuses on the fact that he was moved from the fifth to seventh grade. He identifies this as the cause of his lack of development of social skills, a problem that continues with him to the present. Between the seventh and 12th grade, he perceived "a gradual increasing amount of hostility I had to face from the other kids. By the time I left high school, I was definitely regarded as a freak by a large segment of the student body." He describes a number of incidents in his junior high and high school years, including a discussion of making a small pipe bomb in chemistry, which gained him some notoriety. He described himself as having frustrated resentment towards school, parents, and the student body" which often was given outlet through snotty behavior in the classroom which often took a sarcastic or crudely humorous turn."

[text redacted] He admits that he was "probably a very difficult teenager to live with" and that his parents "were in some respect generous and unselfish." He describes developing a "system of morality that evolved into an abstract artificial construction that could not possibly be applied in practice" but never telling anybody about this system because he knew they would never take it seriously. At the same time, he describes looking for a way to justify hating people. At times in his writings, he focuses, in an extraordinary amount of detail, on passing or short lived relationships or potential relationships with females. This is illustrated by his discussion of his relationship with [text redacted] when he was 10, [text redacted] when he was 16, [text redacted] when he was 17, [text redacted] when he was 32, "Ms. Z" when he was in graduate school, and [text redacted] when he was 36.

Mr. Kaczynski writes about his experiences at Harvard and in essence describes a very isolated existence, with only infrequent interactions with other students. It was not until his sophomore year that he made a few brief friendships, but due to circumstances they did not persist. As noted, in his sophomore year he participated in a research Study at Harvard, conducted by Professor Murray, which looked at the psychological functioning of young men at Harvard.

Mr. Kaczynski claimed in his writing, that during his college years he had fantasies of living a primitive life and fantasized himself as an agitator, rousing mobs to frenzies of revolutionary violence. He claims that during that time he started to think about breaking away from normal society. He describes that beginning in college he began to worry about his health in particular ways, always having a fear-that a symptom could result in something serious. He also claims that during high school and college he would often become terribly angry and because he could not express that anger or hatred openly "I would therefore indulge in fantasies of revenge. However, I never attempted to put any such fantasies into effect because I was too strongly conditioned … against any defiance of authority. To be more precise, I could not have committed a crime of revenge even a relatively minor crime because of my f ear of being caught and punished was all out of proportion to the actual danger of being caught." He describes that as a result, he had little comfort from his fantasies of revenge. He describes a vivid memory of a nightmare in his senior year at Harvard wherein he saw his trombone teacher standing in a room looking like a noble old man, he then saw a mist and heard angels, and when the mist cleared the teacher had been transformed into a bent, senile, old wreck. He describes at length his inability to figure out whether or not he was attractive to women and references a passing comment of a friend of his family’s at the age of 15, that made him believe he was quite attractive.

During the time period after leaving Harvard, he began to study information about wild edible plants, and began to fear the possibility of being drafted. He spent some time hiking and learning about the wilderness.

Upon completion of his work at Harvard, Mr. Kaczynski chose to go to the University of Michigan because it was the only one of the three graduate schools to which he had applied that provided him with a teaching fellowship. He found the teaching—experience difficult and the quality of the program not to his liking. He became involved in some research and succeeded in publishing several papers concerning mathematical theory and problem solving. He describes his work at Michigan as being viewed as exceptional by the instructors. Nonetheless, he also describes having virtually no social life there.

It was during that period of time that he was staying at a rooming house, managed by a graduate student, [text redacted]. He began to experience difficulty with the noise from the other rooms, particularly the sounds resulting from sexual activity of other renters. He reported the noises he heard in the house to the University System, with the hope that action would be taken against Mr. [text redacted]. He describes three experiences where he perceived he overheard the landlord providing negative information about him which subsequently resulted in a negative outcome. The first involved an Engineering student by the name of [text redacted], who was coming over to get help with math problems. Although Mr. Kaczynski couldn’t clearly hear a conversation, he eventually heard a statement by [text redacted] indicating that he had "only come to get help with math. He perceived that Mr. [text redacted] must have said something negative to [text redacted] about him. On the second occasion, he had given an individual information about rooms to rent at the house where he was residing. Again, he heard a voice which he thought belonged to the individual he had spoken with, but he never came up to see him, and the next time he saw him, he was snubbed by him. On the third occasion, he had received a letter from his mother referencing that the daughter of some of their friends was interested in the woods and might like to look him up; they had given her his address. Subsequently, several weeks later he thought he overheard a woman’s voice in the foyer area of the house and Mr. [text redacted] say "oh hi [text redacted]" and then he said something negative about him, and the woman left without ever visiting him.

[text redacted]

He writes, "During my years at Michigan I occasionally began having dreams of a type that I continued to have occasionally over a period of several years. In the dream I would f eel either that organized society was hounding me with accusation in some way, or that organized society was trying in Some way to capture my mind and tie me down psychologically or both. In the most typical form some psychologist or psychologists (often in association with parents or other minions of the system) would either be trying to convince me that I was "sick" or would be trying to control my mind through psychological techniques. I would be on the dodge, trying to escape or avoid the psychologist either physically or in other ways. But I would grow angrier and finally I would break out in physical violence against the psychologist and his allies. At the moment when I broke out into violence and killed the psychologist or other such figure, I experienced a great feeling of relief and liberation. Unfortunately, however, the people I killed usually would spring back to life again very quickly. They just wouldn’t stay dead. I would awake with a pleasurable sense of liberation at having broken into violence, but at the same time with some frustration at the fact that my victims would not stay dead. However, in the course of some dreams, by making a strong effort of will in my sleep, I was able to make my victims stay dead. I think that, as the years went by, the frequency with which I was able to make my victims stay dead through exertion of will increased." In the same period of time he experienced low morale and mood.

In the summer after his fourth year, he describes experiencing a period of several weeks where he was sexually excited nearly all the time and was fantasizing himself as a woman and being unable to obtain any sexual relief. He decided to make an effort to have a sex change operation. When he returned to the University of Michigan he made an appointment to see a psychiatrist to be examined to determine if the sex change would be good for him. He claimed that by putting on an act he could con the psychiatrist into thinking him suitable for a feminine role even though his motive was exclusively erotic. As he was sitting in the waiting room, he turned completely against the idea of the operation and thus, when he saw the doctor, instead claimed he was depressed about the possibility of being drafted. He describes the following: As I walked away from the building afterwards, I felt disgusted about what my uncontrolled sexual cravings had almost led me to do and I felt – humiliated, and I violently hated the psychiatrist. Just then there came a major turning point in my life. Like a Phoenix, I burst from the ashes of my despair to a glorious new hope. I thought I wanted to kill that psychiatrist because the future looked utterly empty to me. I felt I wouldn’t care if I died. And so I said to myself why not really kill the psychiatrist and anyone else whom I hate. What is important is not the words that ran through my mind but the way I felt about them. What was entirely new was the fact that I really felt I could kill someone. My very hopelessness had liberated me because I no longer cared about death. I no longer cared about consequences and I said to myself that I really could break out of my rut in life and do things that were daring, irresponsible or criminal. He describes his first thought was to kill someone he hated and then kill himself, but decided he could not relinquish his rights so easily. At that point he decided: I will kill but I will make at least some effort to avoid detection so that I can kill again.,, He decided that he would do what he always wanted to do, to go to Canada to take off in the woods with a rifle and try to live off the country. "If it doesn’t work and if I can get back to civilization before I starve then I will come back here and kill someone I hate. 11 In his writings he emphasized what he knew was the fact that he now felt he had the courage to behave irresponsibly.

Mr. Kaczynski describes in his writing and on interview, that these thoughts went through his mind in the time it took to walk about one block. This new understanding persisted from that point on in his life. He developed a plan to complete his degree and to work for two years, so as to save enough money to live in the wilderness. As already noted, this plan was accomplished through teaching for two years in Berkeley and subsequently locating land and building his cabin in Montana. During that time period he writes that he would have to discipline himself to avoid reading newspapers except occasionally because if ‘I read papers regularly I would build up too much tense and frustrated anger against Politicians, dictators, businessmen, scientists, communists, and others in the world who were doing things that endangered me or changed the world in ways I resented.?’

http://www.paulcooijmans.com/psychology … eport.html

I don’t think he wrote the Mad is the Word because it says right here that he skipped 6th grade, unless he is calling it 6th grade? It does sound like it was a hard year for him.

"Mr. Kaczynski attended kindergarten and grades one through four at Sherman Elementary school in Chicago. He attended fifth through eighth grade at Evergreen Park Central school. As the result of testing conducted in the fifth grade, it was determined that he could skip the sixth grade and enroll with the seventh grade class. According to various accounts, testing showed him to have a high IQ and, by his account, his parents were told he was a genius. He claims that his IQ was in the 160 to 170 range. Testing supposedly conducted at that time has not been made available for review. Mr. Kaczynski described this skipping a grade as a pivotal event in his life. He remembers not fitting in with the older children and being the subject of considerable verbal abuse and teasing from them. He did not describe having any close friends during that period of time."

More psychological information.

Introduction

Ted Kaczynski wrote this letter in reply to a Turkish anarchist, Kara, who sent him a series of questions as an interview for her zine. Rather than include Kara’s letter, I have quoted only the questions which Kaczynski answered. Spelling and typographical errors, apparently introduced in transcription, have been fixed. Kara’s English has been corrected. Section headings have been added.

In the letter, Kaczynski describes his personal motivation for absconding from civilization; he quotes from his journal to explain his motive for seeking its destruction; he asserts the responsibility of technology for civilization; he addresses the idea of non-violence as a value in itself; he rebuts the romanticized vision of primitive society promoted by some primitivists; and he warns against the counter-revolutionary potential of the “Green Anarchist Movement,” which he attributes to the influence of leftist values.

Regarding his bombings, Kaczynski claims here that he sought to destroy industrial society only after the land on which he had escaped it was destroyed by development.

The letter follows.

Dear Kara,

I am sorry I have taken so long to answer your letter dated August 12. I am usually busy, especially with answering correspondence, and your letter is one that could not be answered hastily, because some of your questions require long, complicated, carefully-considered answers.

For this same reason, it would cost me an unreasonable amount of time to answer all of your questions. So I will answer only some of them — the ones that seem to me to be most important and those that can be answered easily and briefly.

Biographical

Kara: Where/when were you born?

I was born in Chicago, Illinois, U.S.A., on May 22, 1942.

Kara: Which schools did you graduate from?

I graduated from an elementary school and a high school in Evergreen Park, Illinois. I received a bachelors degree from Harvard University, and masters degree and doctors degree in mathematics from the University of Michigan.

Kara: What was your job?

After receiving my doctors degree from the University of Michigan, I was an assistant professor of mathematics for two years at the University of California.

Kara: Were you married? Do you have children?

I have never been married and have no children.

Rejecting civilization

Kara: You were a mathematician — do you have thoughts like that now? What has changed your ideas wholly? When did you start to think that the problem is in civilisation? Can you tell in a few words why you refused civilisation? How/when did you decide to live in the forest?

A complete answer to these questions would be excessively long and complicated, but I will say the following:

The process through which I came to reject modernity and civilization began when I was eleven years old. At that age I began to be attracted to the primitive way of life as a result of reading of the life of Neanderthal man. In the following years, up to the time when I entered Harvard University at the age of sixteen, I used to dream of escaping from civilization and going to live in some wild place. During the same period, my distaste for modern life grew as I became increasingly aware that people in industrial society were reduced to the status of gears in a machine, that they lacked freedom and were at the mercy of the large organizations that controlled the conditions under which they lived.

After I entered Harvard University I took some courses in anthropology, which taught me more about primitive peoples and gave me an appetite to acquire some of the knowledge that enabled them to live in the wild. For example, I wished to have their knowledge of edible plants. But I had no idea where to get such knowledge until a couple of years later, when I discovered to my surprise that there were books about edible wild plants. The first such a book that I bought was Stalking the Wild Asparagus, by Euell Gibbons, and after that when I was home from college and graduate school during the summers, I went several times each week to the Cook County Forest Preserves near Chicago to look for edible plants. At first it seemed eerie and strange to go all alone into the forest, away from all roads and paths. But as I came to know the forest and many of the plants and animals that lived in it, the feeling of strangeness disappeared and I grew more and more comfortable in the woodland. I also became more and more certain that I did not want to spend my whole life in civilization, and that I wanted to go and live in some wild place.

Meanwhile, I was doing well in mathematics. It was fun to solve mathematical problems, but in a deeper sense mathematics was boring and empty because for me it had no purpose. If I had worked on applied mathematics I would have contributed to the development of the technological society that I hated, so I worked only on pure mathematics. But pure mathematics was only a game. I did not understand then, and I still do not understand, why mathematicians are content to fritter away their whole lives in a mere game. I myself was completely dissatisfied with such a life. I knew what I wanted: to go and live in some wild place. But I didn’t know how to do so. In those days there were no primitivist movements, no survivalists, and anyone who left a promising career in mathematics to go live among forests or mountains would have been regarded as foolish or crazy. I did not know even one person who would have understood why I wanted to do such a thing. So, deep in my heart, I felt convinced that I would never be able to escape from civilization.

Because I found modern life absolutely unacceptable, I grew increasingly hopeless until, at the age of 24, I arrived at a kind of crisis: I felt so miserable that I didn’t care whether I lived or died. But when I reached that point, a sudden change took place: I realized that if I didn’t care whether I lived or died, then I didn’t need to fear the consequences of anything I might do. Therefore I could do anything I wanted. I was free! That was the great turning-point in my life because it was then that I acquired courage, which has remained with me ever since. It was at that time, too, that I became certain that I would soon go to live in the wild, no matter what the consequences. I spent two years teaching at the University of California in order to save some money, then I resigned my position and went to look for a place to live in the forest.

Motivation for bombing

Kara: How/when did you decide to bomb?

It would take too much time to give a complete answer to the last part of your ninth question, but I will give you a partial answer by quoting what I wrote for my journal on August 14, 1983:

The fifth of August I began a hike to the east. I got to my hidden camp that I have in a gulch beyond what I call “Diagonal Gulch.” I stayed there through the following day, August 6. I felt the peace of the forest there. But there are few huckleberries there, and though there are deer, there is very little small game. Furthermore, it had been a long time since I had seen the beautiful and isolated plateau where the various branches of Trout Creek originate. So I decided to take off for that area on the 7th of August. A little after crossing the roads in the neighborhood of Crater Mountain I began to hear chain saws; the sound seemed to be coming from the upper reaches of Roaster Bill Creek. I assumed they were cutting trees; I didn’t like it but I thought I would be able to avoid such things when I got onto the plateau. Walking across the hillsides on my way there, I saw down below me a new road that had not been there previously, and that appeared to cross one of the ridges that close in Stemple Creek. This made me feel a little sick. Nevertheless, I went on to the plateau. What I found there broke my heart. The plateau was criss-crossed with new roads, broad and well-made for roads of that kind. The plateau is ruined forever. The only thing that could save it now would be the collapse of the technological society. I couldn’t bear it. That was the best and most beautiful and isolated place around here and I have wonderful memories of it.

One road passed within a couple of hundred feet of a lovely spot where I camped for a long time a few years ago and passed many happy hours. Full of grief and rage I went back and camped by South Fork Humbug Creek.

The next day I started for my home cabin. My route took me past a beautiful spot, a favorite place of mine where there was a spring of pure water that could safely be drunk without boiling. I stopped and said a kind of prayer to the spirit of the spring. It was a prayer in which I swore that I would take revenge for what was being done to the forest.

My journal continues: “[…] and then I returned home as quickly as I could because I have something to do!”

You can guess what it was that I had to do.

Technology and civilization

Kara: What made you decide to bomb technological areas? How do you think we can we destroy civilisation? What will make its destruction closer?

Anything like a complete answer to these questions would take too much time. But the following remarks are relevant:

The problem of civilization is identical with the problem of technology. Let me first explain that when I speak of technology I do not refer only to physical apparatus such as tools and machines. I include also techniques, such as the techniques of chemistry, civil engineering, or biotechnology. Included too are human techniques such as those of propaganda or of educational psychology, as well as organizational techniques that could not exist at an advanced level without the physical apparatus — the tools, machines, and structures — on which the whole technological system depends.

However, technology in the broader sense of the word includes not only modern technology but also the techniques and physical apparatuses that existed at earlier stages of society. For example, plows, harnesses for animals, blacksmiths tools, domesticated breed of plants and animals, and the techniques of agriculture, animal husbandry, and metalworking. Early civilizations depended on these technologies, as well as on the human and organizational techniques needed to govern large numbers of people. Civilizations cannot exist without the technology on which they are based. Conversely, where the technology is available civilization is likely to develop sooner or later.

Thus, the problem of civilization can be equated with the problem of technology. The farther back we can push technology, the father back we will push civilization. If we could push technology all the way back to the stone age, there would be no more civilization.

Violence

Kara: Don’t you think violence is violence?

In reference to my alleged actions you ask, “Don’t you think violence is violence?” Of course, violence is violence. And violence is also a necessary part of nature. If predators did not kill members of prey species, then the prey species would multiply to the point where they would destroy their environment by consuming everything edible. Many kinds of animals are violent even against members their own species. For example, it is well known that wild chimpanzees often kill other chimpanzees. See, e.g., Time Magazine, August 19, 202, page 56. In some regions, fights are common among wild bears. The magazine Bear and Other Top Predators, Volume 1, Issue 2, pages 28–29, shows a photograph of bears fighting and a photograph of a bear wounded in a fight, and mentions that such wounds can be deadly. Among the sea birds called brown boobies, two eggs are laid in each nest. After the eggs are hatched, one of the young birds attacks the other and forces it out of the nest, so that it dies. See article “Sibling Desperado,” Science News, Volume 163, February 15, 2003.

Human beings in the wild constitute one of the more violent species. A good general survey of the cultures of hunting-and-gathering people is The Hunting Peoples, by Carleton S. Coon, published by Little, Brown and Company, Boston and Toronto, 1971, and in this book you will find numerous examples in hunting-and-gathering societies of violence by human beings against other human beings. Professor Coon makes clear (pages XIX, 3, 4, 9, 10) that he admires hunting-and-gathering peoples and regards them as more fortunate than civilized ones. But he is an honest man and does not censor out those aspects of primitive life, such as violence, that appear disagreeable to modern people.

Thus, it is clear that a significant amount of violence is a natural part of human life. There is nothing wrong with violence in itself. In any particular case, whether violence is good or bad depends on how it is used and the purpose for which it is used.

So why do modern people regard violence as evil in itself? They do so for one reason only: they have been brainwashed by propaganda. Modern society uses various forms of propaganda to teach people to be frightened and horrified by violence because the technoindustrial system needs a population that is timid, docile, and afraid to assert itself, a population that will not make trouble or disrupt the orderly functioning of the system. Power depends ultimately on physical force. By teaching people that violence is wrong (except, of course, when the system itself uses violence via the police or the military), the system maintains its monopoly on physical force and thus keeps all power in its own hands.

Whatever philosophical or moral rationalizations people may invent to explain their belief that violence is wrong, the real reason for that belief is that they have unconsciously absorbed the system’s propaganda.

Green Anarchism

Kara: How do you see anarchists, green-anarchists, anarcho-primitivists? Do you agree with them? How do you see vegetarianism/veganism? What do you think about refusing to eat and use animals? What do you think about Animal/Earth Liberation? What do you think about groups such as Earth First!, Earth Liberation Front and Gardening Guerillas?

All of the groups you mention here are part of a single movement. (Let’s call it the “Green Anarchist” (GA) Movement). Of course, these people are right to the extent that they oppose civilization and the technology on which it is based. But, because of the form in which this movement is developing, it may actually help to protect the technoindustrial system and may serve as an obstacle to revolution. I will explain:

It is difficult to suppress rebellion directly. When rebellion is put down by force, it very often breaks out again later in some new form in which the authorities find it more difficult to control. For example, in 1878 the German Reichstag enacted harsh and repressive laws against Social-Democratic movement, as a result of which the movement was crushed and its members were scattered, confused, and discouraged. But only for a short time. The movement soon reunited itself, became more energetic, and found new ways of spreading its ideas, so that by 1884 it was stronger than ever. G. A. Zimmermann, Das Neunzehnte Jahrhundert: Geshichtlicher und kulturhistorischer Rückblick, Druck und Verlag von Geo. Brumder, Milwaukee, 1902, page 23.

Thus, astute observers of human affairs know that the powerful classes of a society can most effectively defend themselves against rebellion by using force and direct repression only to a limited extent, and relying mainly on manipulation to deflect rebellion. One of the most effective devices used is that of providing channels through which rebellious impulses can be expressed in ways that are harmless to the system. For example, it is well known that in the Soviet Union the satirical magazine Krokodil was designed to provide an outlet for complaints and for resentment of the authorities in a way that would lead no one to question the legitimacy of the Soviet system or rebel against it in any serious way.

But the “democratic” system of the West has evolved mechanisms for deflecting rebellion that are far more sophisticated and effective than any that existed in the Soviet Union. It is a truly remarkable fact that in modern Western society people “rebel” in favor of the values of the very system against which they imagine themselves to be rebelling. The left “rebels” in favor of racial and religious equality, equality for women and homosexuals, humane treatment of animals, and so forth. But these are the values that the American mass media teach us over and over again every day. Leftists have been so thoroughly brainwashed by media propaganda that they are able to “rebel” only in terms of these values, which are values of the technoindustrial system itself. In this way the system has successfully deflected the rebellious impulses of the left into channels that are harmless to the system.

Primitive society

The romanticized vision

Rebellion against technology and civilization is real rebellion, a real attack on the values of the existing system. But the green anarchist, anarcho-primitivists, and so forth (the “GA Movement”) have fallen under such heavy influence from the left that their rebellion against civilization has to a great extent been neutralized. Instead of rebelling against the values of civilization, they have adopted many civilized values themselves and have constructed an imaginary picture of primitive societies that embodies these civilized values. They pretend that hunter-gatherers worked only two or three hours a day (which would come to 14 to 21 hours a week), that they had gender equality, that they respected the rights of animals, that they took care not to damage their environment, and so forth. But all that is a myth. If you will read many reports written by people who personally observed hunting-and-gathering societies at a time when these were relatively free of influence from civilization, you will see that:

All of these societies ate some form of animal food, none were vegan.

Most (if not all) of these societies were cruel to animals.

The majority of these societies did not have gender equality.

The estimate of two or three hours of work a day, or 14 to 21 hours per week, is based on a misleading definition of “work.” A more realistic minimum estimate for fully nomadic hunter-gatherers would probably be about forty hours of work per week, and some worked a great deal more than that.

Most of these societies were not nonviolent.

Competition existed in most, or probably all of these societies. In some of them competition could take violent forms.

These societies varied greatly in the extent to which they took care not to damage their environment. Some may have been excellent conservationists, but others damaged their environment through over-hunting, reckless use of fire, or in other ways.

I could cite numerous reliable sources of information in support of the foregoing statements, but if I did so this letter would become unreasonably long. So I will reserve full documentation for a more suitable occasion. Here I mention only a few examples.

Cruelty to animals

Mbuti pygmies:

The youngster had spread it with his first thrust, pinning the animal to the ground through the fleshy part of the stomach. But the animal was still very much alive, fighting for freedom. […] Maipe put another spear into its neck, but it still writhed and fought. Not until a third spear pierced its heart did it give up the struggle. […] [T]he Pygmies stood around in an excited group, pointing at the dying animal and laughing. At other times I have seen Pygmies singeing the feathers off birds that were still alive, explaining that the meat is more tender if death comes slowly. And the hunting dogs, valuable as they are, get kicked around mercilessly from the day they are born to the day die.

— Colin Turnbull, The Forest People, Simon and Schuster, 1962, page 101.

Eskimos: The Eskimos with whom Gontran de Poncins lived kicked and beat their dogs brutally. Gontran de Poncins, Kabloona, Time-Life Books, Alexandria, Virginia, 1980, pages 29, 30, 49, 189, 196, 198–99, 212, 216.

Siriono: The Siriono sometimes captured young animals alive and brought them back to camp, but they gave them nothing to eat, and the animals were treated so roughly by the children that they soon died. Allan R. Holmberg, Nomads of the Long Bow: The Siriono of Eastern Bolivia, The Natural History Press, Garden City, New York, 1969, pages 69–70, 208. (The Siriono were not pure hunter-gatherers, since they did plant crops to a limited extent at certain times of year, but they lived mostly by hunting and gathering. Holmberg, pages 51, 63, 67, 76–77, 82–83, 265.)

Lack of gender equality

Mbuti pygmies: Turnbull says that among the Mbuti, “A woman is in no way the social inferior of a man” (Colin Turnbull, Wayward Servants, The Natural History Press, Garden City, New York, 1965, page 270), and that “the woman is not discriminated against” (Turnbull, Forest People, page 154). But in the very same books Turnbull states a number of facts that show that the Mbuti did not have gender equality as that term is understood today. “A certain amount of wife-beating is considered good, and the wife is expected to fight back.” Wayward Servants, page 287. “He said that he was very content with his wife, and he had not found it necessary to beat her at all often.” Forest People, page 205. Man throws his wife to the ground and slaps her.

Wayward Servants, page 211. Husband beats wife. Wayward Servants, page 192. Mbuti practice what Americans would call “date rape.” Wayward Servants, page 137. Turnbull mentions two instances of men giving orders to their wives. Wayward Servants, page 288–89; Forest People, page 265. I have not found any instance in Turnbull’s books of wives giving orders to their husbands.

Siriono: The Siriono did not beat their wives. Holmberg, page 128. But: “A woman is subservient to her husband.” Holmberg, page 125. “The extended family is generally dominated by the oldest active male.” Page 129. “[W]omen […] are dominated by the men.” Page 147. “Sexual advances are generally made by the men. […] If a man is out in the forest alone with a woman he may throw her to the ground roughly and take his prize without so much saying a word.” Page 163. Parents definitely prefer to have male children. Page 202. Also see pages 148, 156, 168–69, 210, 224.

Australian Aborigines: “Farther north and west [in Australia] […]

erceptible power lay in the hands of the mature, fully initiated, and usually polygynous men of the age group from thirty to fifty, and the control over the women and younger males was shared between them.” Carleton S. Coon, The Hunting Peoples (cited earlier), page 255. Among some Australian tribes, young women were forced to marry old men, mainly so that they should work for the men. Women who refused were beaten until they gave in. See Aldo Massola, The Aborigines of South-Eastern Australia: As They Were, The Griffin Press, Adelaide, Australia, 1971. I don’t have the exact page, but you will probably find the foregoing between pages 70 and 80.

Time spent working