Are you saying Zodiac:

1. Made all his characters on a typewriter?

The more I look into it, the more certain features of the ciphers make a lot more sense if this is the case. I don’t think the ciphers are "typewritten", though. There is a different process for making copies on a typewriter than we’re used to thinking about today. It involved the use of a stencil sheet that you put into a typewriter and then ran through a machine called a mimeograph. However, since these stencils were basically a special kind of paper, it was possible and, in fact, fairly common to use another device called a mimeoscope (which is basically a lightbox), and a special kind of stylus to make alterations by hand.

Here’s a video from 1958 that shows how it worked: https://youtu.be/gYjj62eGwc8

Another thing that you can do with a typewriter is you can actually take the paper out, flip it over rotate it, then put it back in. Since the paper feed is controlled manually you have a lot more control over where letters strike the page. Since there is nothing stopping you from typing a letter on a space that you’ve already typed on, by rotating the paper and flipping it over in various ways, using the typeface that I suggested above, it should be possible to recreate every symbol on that page. That is with three exceptions. My working theory, right now, is that the cipher was drafted on a typewriter using layers of a type of paper called "onionskin." The author then would have taken that paper to a mimeoscope and traced the symbols onto a stencil sheet in order to disguise the fact that this process was used as well as identifying features of his typewriter.

I’m spitballing in this thread to an extent, but this would offer a pretty plausible explanation for the consistency in dimensions that you see in the 408. I don’t know if my printout is the same size as the original, but I just got done measuring the 340 and from top to bottom it is 5 lines per 1.5 inches and from side to side it is 4 symbols for every 1.25 inches. Additionally, from top to bottom the 340 is 7.5 inches wich would make it possible to insert paper into the typewriter sideways if the original draft had been cut. You can check those dimensions yourself, it’s pretty crazy. The fact that a Saks Fifth Avenue watermark has been found on the 340 adds a lot of potential to this idea as they were well known enough for selling typing paper that, in 2018, "onionskin" was used as a crossword clue in the LA Times with the answer being "Saks Fifth Avenue"

2. Chose his substitutions based on the standard keyboard arrangement?

It isn’t clear yet. I don’t have an answer that I could stand behind confidently but I’m working on it.

3. Typed up his cipher while looking at a separate key?

I don’t know

4. This separate key was oriented vertically, but not A-Z. Rather he had the alphabet in order of the letters with the greatest number of substitutions?

I also don’t know the answer to this question. Right now I’m trying to see if I can look at some patterns in the encryption of the cipher and back engineer to probable layout of his key but it’s kind of like trying to guess the brand of a boat from the waves it makes. I’m working on it, even if I’m probably not qualified, I don’t see the harm in giving it a try.

It’s an interesting observation. I wonder if the keyboard layout really did play a role in him making the cipher key. It’s hard to tell since a lot of the key doesn’t seem related to the layout.

So the observation is that (some) of the letters and their respective homophone mappings sit next/close/adjacent to each other on a Qwerty keyboard?

Have the odds ever been calculated?

So the observation is that (some) of the letters and their respective homophone mappings sit next/close/adjacent to each other on a Qwerty keyboard?

Yes

Have the odds ever been calculated?

As far as I know, they have not.

My guess is that a shuffle study would show it would happen by chance fairly often.

But, the cluster of homophones for the letter I stands out a bit.

Here’s the thing; I understand why he would mix up "A" with "S" when he messed up [MOST] and [MOAT]. A-4 and S-4 are both triangles.

But why exactly is he mixing up "O" and "T" as well as "E" and "S" in [DANGEROUS]/[DANGERTUE]?

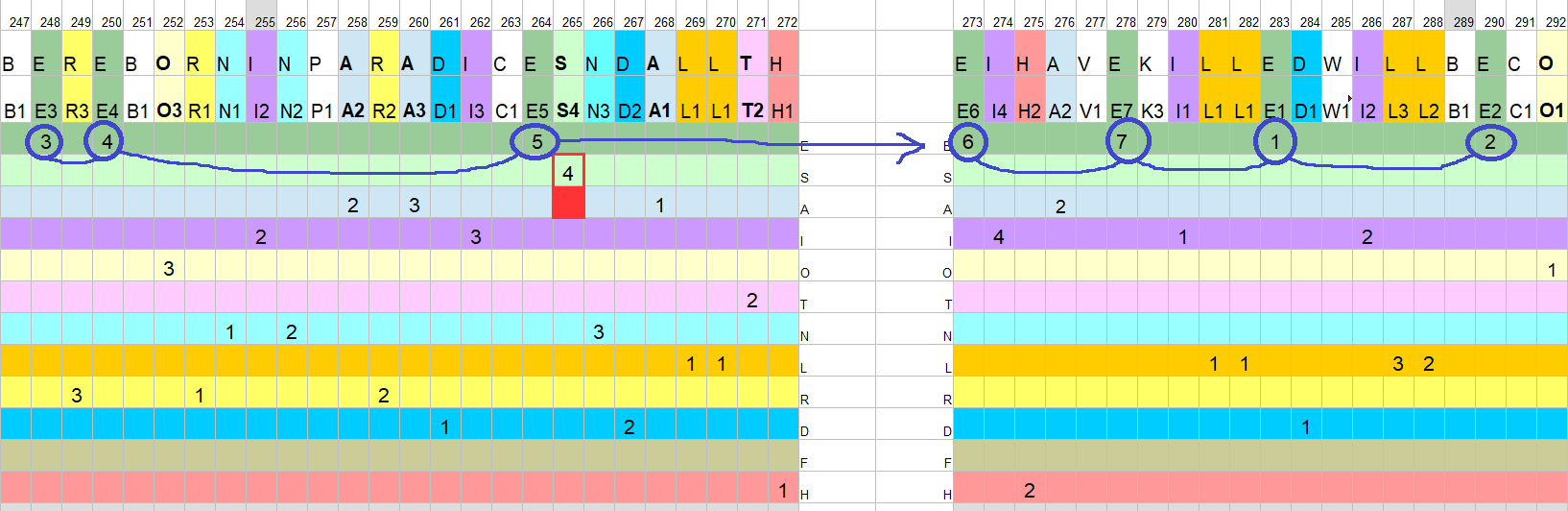

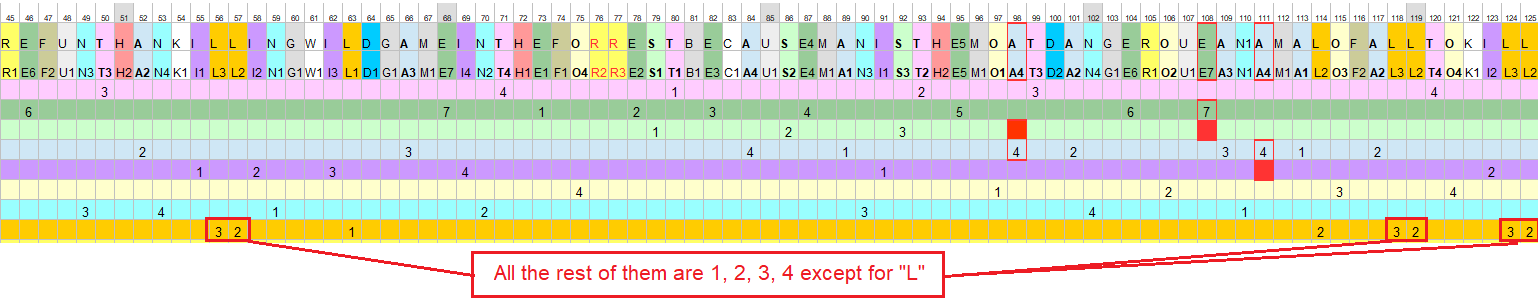

I have gone through the 408 and it is hard not to conclude that, at least in the first two parts, he is systematically going through his list of homophones when he makes his substitutions.* This is the order as they are substituted in 408 for those letters:

I do not understand how, if he is doing this systematically and keeping track of where he is with each letter and their substitutions that he is also going to confuse homophones just because they look similar. That is unless they are organized in his key in such a way that he is causing them to get mixed up, i.e., close to one another. If he’s keeping track of the cycles, why is he also going to end up substituting the wrong letter? If he is reading off a table of substitutions, don’t "E" and "S" and "A" and "S" have to be basically next to eachother?

Isn’t it also a little odd then that, if you omit the plaintext substitution header from this key and only include the actual substitutions, E-5 [O dot] and O-3 [T] are the same vertical distance from E, and S1 and E7 are right next to each other and he is mixing all of these up over the course of 3 substitutions?

Also, grab a ruler some time and actually measure the relative spacing between lines and columns in these ciphers. It is one thing to keep things neat and tidy in small groups, but when it is the same spacing at the beginning as at the end, how does that happen by accident? Why is this person being so meticulous about the layout of the cipher but so disorganized as to have a key that he can’t read?

It is utterly bizarre. I don’t get it. Who is this person?

*The exception is "L." I don’t know what the deal is with L unless those substitution actually began their lives as , [N] and [M]

EDIT: Also, being a substitution for "A" is just too weird.

I do not understand how, if he is doing this systematically and keeping track of where he is with each letter and their substitutions that he is also going to confuse homophones just because they look similar. That is unless they are organized in his key in such a way that he is causing them to get mixed up, i.e., close to one another. If he’s keeping track of the cycles, why is he also going to end up substituting the wrong letter? If he is reading off a table of substitutions, don’t "E" and "S" and "A" and "S" have to be basically next to eachother?

In function of forming a hypothesis: We can conclude that the letters O/T and A/S sat close to each other in a vertical table. And that the horizontal ordering was thus by number of homophones or frequency. It’s really interesting.

I am not in favor of E and S being confused this way but it is possible.

Isn’t it also a little odd then that, if you omit the plaintext substitution header from this key and only include the actual substitutions, E-5 [O dot] and O-3 [T] are the same vertical distance from E, and S1 and E7 are right next to each other and he is mixing all of these up over the course of 3 substitutions?

I don’t quite understand sorry. But I would say it is not improbable to mix these up.

Also, grab a ruler some time and actually measure the relative spacing between lines and columns in these ciphers. It is one thing to keep things neat and tidy in small groups, but when it is the same spacing at the beginning as at the end, how does that happen by accident? Why is this person being so meticulous about the layout of the cipher but so disorganized as to have a key that he can’t read?

Of course the presentation of the cipher was crucial if Zodiac were to be successful in captivating the crowd. In my eyes, the relatively few mistakes he made don’t mean anything. The cipher text and it’s plain text are of very good overall quality.

During the time when classical cryptography was employed it was considered a plus when a cryptographic system was tolerant to mistakes (I think especially in a military setting, because people do make mistakes).

EDIT: Also,

being a substitution for "A" is just too weird.

Why? The letters can be close to each other (4 homophones each) and are both on the 4th vertical position.

I am not in favor of E and S being confused this way but it is possible.

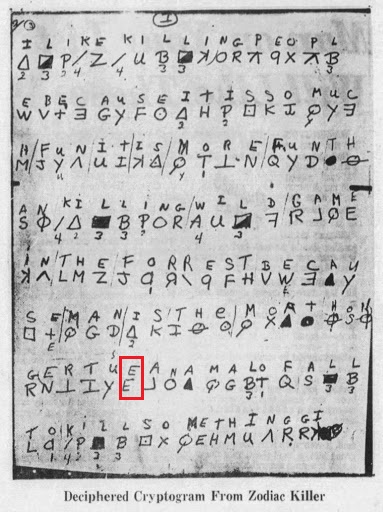

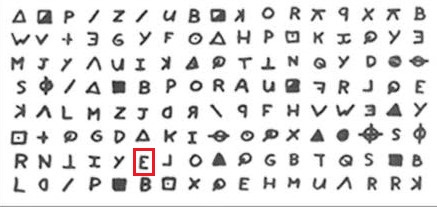

This literally happened

Yes, but that does not mean that he mixed up E and S per se. Letters E and F are similar.

does not mean that he mixed up E and S per se. Letters E and F are similar.

Jarlve, please. The distinction between a plaintext letter and its homophonic substitutions is not lost on me. I do not know how to help you understand that this person is methodically substituting homophones from his key without showing you a big table of data. The last time I did that it confused the heck out of everyone, so I’m trying really hard not to just waste everyone’s time and patience here. All I’m saying is that it’s weird when the author of this cipher means to put down S1 and instead puts down E7. It is weird that E7 and S1 are even close enough to eachother to mix up because every one of these homophonic substitutions start in one place and keep coming back to their starting position.

The exceptions are E and L. L is weird. I’m not ready to talk about L. I don’t understand what is happening with L. But E1, the very first substitution he makes for "E", is [Z], and the cycle that keeps popping up is [ZPW+ONE]*. I would like to have a more comprehensive understanding of why this person starts with [Z] for "E" and [F] for "S" then mixes up the two because, as I’m sure you’ve noticed, [+] is right in the middle of that cycle and, for whatever reason, our cryptic friend here has a lot of those in the 340 ( a surPLUS if you will). If there is something going on with [E] in the 408, that might help better specify the unique properties of 340.

My last point here: 3 months. That’s how long this person has to experience a complete paradigm shift in their ability to create a homophonic substitution cipher. I don’t know if the 408 represents this person’s best work or his least effort. It matters if he misspells one word on accident and then misspells the very next word on purpose, especially if he is literate enough to recognize and use [YOUR] in its proper context.

ALSO: both times he does the [MOAT] thing it comes with an A4T3 bigram (Triangle-Circle). WEIRD. I’m not digging through the Rubiyat to find an explanation for what I’m seeing here, I don’t know why, but it’s in the cipher.

*obviously the P is backwards

Jarlve, please. The distinction between a plaintext letter and its homophonic substitutions is not lost on me. I do not know how to help you understand that this person is methodically substituting homophones from his key without showing you a big table of data. The last time I did that it confused the heck out of everyone, so I’m trying really hard not to just waste everyone’s time and patience here. All I’m saying is that it’s weird when the author of this cipher means to put down S1 and instead puts down E7. It is weird that E7 and S1 are even close enough to eachother to mix up because every one of these homophonic substitutions start in one place and keep coming back to their starting position.

Of course not. I am just trying to say that he may have chosen S1 correctly but err’d while drawing making the letter E instead.

He just keeps going. I guess if he did skip a line, it’s more likely to have been during encryption than after it (if he recopied the cipher text at some point.)

Good point! Well spotted.

Did you know that he intentionally created matching double L bigrams in the first part?

Except for the first LL:

L LL L LL L L LL LL 1 21 2 32 1 2 32 32

There are 9 possible bigrams out of 3 symbols:

11,22,33 12,21 23,32 13,31

1-gram frequencies for each homophone show flat distribution:

Homophone: frequency -------------------- 2: 12 1: 11 3: 10

2-gram frequencies (bigrams) for full L homophone sequence "121232123232321321111323211323312" shows preference to "32" bigram. And only 5 out of the possible 9 bigrams have formed:

Bigram: frequency ----------------- 32: 8 23: 6 21: 5 12: 4 11: 4

– There may be something to your "32" bigram observation.

– The full L homophone sequence "1212321…" with my 2-symbol cycle measurement scores 12. Only 63 out of 10000 shuffles have 12 or better thus the sequence is cyclic although imperfect.

– The "slope" of the sequence "1212321…" is -1. For example, the sequence "123123123123123" has a positive slope since it goes uphill and "321321321" has a negative slope since it goes downhill. The L homophones not having a positive slope may indicate that Zodiac did not pick these homophones from left-to-right from a table, but since we know the sequence is cyclic it must have meant that he at least tried to alternate the homophones to some extent. Interesting!

Bigram: frequency ----------------- 32: 8 23: 6 21: 5 12: 4 11: 4

The frequency for 23 wouldn’t tell you exactly the distribution of 23 bigrams in the cipher though, would it? I know 23 shows up when the substitution sequence is consolidated and then analyzed, but if I’m trying to hide the letter frequency for L, especially when it comes to double L, wouldn’t it be in my best interest to have the flattest possible distribution between 12, 13, 31, 21, 23, and 32 bigrams? By my count, 23 only shows up inside the full ciphertext once in the entire cipher and 21 is only twice versus 6 times for 32.

I don’t know how these things are usually analyzed but is it really behaving like a military encryption or is it more like a newspaper cipher puzzle with little hints and clues in it? If I’m wrong that’s fine but there seems like a huge preference for order towards the beginning rather than the end. That’s instead of what I imagine non-crappy encryption would look like (i.e. as flat as possible).

Also the 11 bigrams (for double L substitutions) only show up just before the end of the second part. I would think another sequence you would really want to measure (although I’m not insisting) would be 213232323232111132211323 because at least that would tell you what he was focusing on if he really cared about hiding his double L’s, although it might still over-represent the 23s.

I really don’t know much about traditional encryption beyond the basics, but I do know puzzles and in a lot of ways this seems like one.

– There may be something to your "32" bigram observation.

– The full L homophone sequence "1212321…" with my 2-symbol cycle measurement scores 12. Only 63 out of 10000 shuffles have 12 or better thus the sequence is cyclic although imperfect.

– The "slope" of the sequence "1212321…" is -1. For example, the sequence "123123123123123" has a positive slope since it goes uphill and "321321321" has a negative slope since it goes downhill. The L homophones not having a positive slope may indicate that Zodiac did not pick these homophones from left-to-right from a table, but since we know the sequence is cyclic it must have meant that he at least tried to alternate the homophones to some extent. Interesting!

If we were feeling especially generous and decided to fix his mistakes, the rest of the homophone sequences, excluding cipher characters 99, 108, 111, 147, 229, 233 and 265 (i.e. the substitution errors and not necessarily spelling errors in the plaintext), I think you would see perfect cycles for every substitution except for "L." That’s what I’m seeing in my data. Of course, that is in parts 1 and 2 because part 3 is weird and stupid and I hate everything about it and so should everyone else (kidding).

Man I’m having so much fun. This is like Bletchley Park minus all the bad parts (i.e. bombing raids, espionage, tea). ![]()

**It’s been years and I know you guys have been tearing these ciphers apart for a long time before I got here. Just trying to help because I do like puzzles and I don’t like homicides. Thanks for running some tests on the data, Jarlve.

The frequency for 23 wouldn’t tell you exactly the distribution of 23 bigrams in the cipher though, would it? I know 23 shows up when the substitution sequence is consolidated and then analyzed, but if I’m trying to hide the letter frequency for L, especially when it comes to double L, wouldn’t it be in my best interest to have the flattest possible distribution between 12, 13, 31, 21, 23, and 32 bigrams? By my count, 23 only shows up inside the full ciphertext once in the entire cipher and 21 is only twice versus 6 times for 32.

Not sure what you mean with the first question. Yes, a flat distribution between 12, 13, 31, 21, 23 and 32 etc is of best interest for hiding doubles. Are you counting by double L’s? In my previous table, I mistakenly counted bigram repeats instead of bigram frequencies. Here’s a new table:

Bigram frequencies for double L: 21: 2 32: 4 11: 2 13: 2 33: 1 L LL L LL L L LL LL L L L LL LL LL L L L LL LL L LL L L 1 21 2 32 1 2 32 32 3 2 1 32 11 11 3 2 3 21 13 2 33 1 2 % B% B #B % B #B #B # B % #B %% %% # B # B% %# B ## % B

I don’t know how these things are usually analyzed but is it really behaving like a military encryption or is it more like a newspaper cipher puzzle with little hints and clues in it? If I’m wrong that’s fine but there seems like a huge preference for order towards the beginning rather than the end. That’s instead of what I imagine non-crappy encryption would look like (i.e. as flat as possible).

Perhaps both the military encryption or newspaper cipher are not good fits. The Z408 is actually reasonably flat – measured on a 0 to 1 scale where 1 is totally flat such that each symbols occurs exactly equally – it scores 0.83. The Z340 is 0.73. A resubstitution of the Z408 plain text with 54 symbols and perfect cycles gives a 0.92. The Z408 plain text is 0.66, which is average for plain texts.

If we were feeling especially generous and decided to fix his mistakes, the rest of the homophone sequences, excluding cipher characters 99, 108, 111, 147, 229, 233 and 265 (i.e. the substitution errors and not necessarily spelling errors in the plaintext), I think you would see perfect cycles for every substitution except for "L." That’s what I’m seeing in my data.

That’s really interesting. I wonder what’s up with L, you may start to think he wanted to give a hint.

Not sure what you mean with the first question. Yes, a flat distribution between 12, 13, 31, 21, 23 and 32 etc is of best interest for hiding doubles. Are you counting by double L’s? In my previous table, I mistakenly counted bigram repeats instead of bigram frequencies.

This answered my question. I was talking about the double "LL"s and not the overall cycling behavior for "L." It seems like the lack of flatness in bigrams frequencies for"LL" is unique to this letter, and it would seem like an intentional clue, but this is also what drives me nuts about 408, because there is a solid case that he might have realized that he didn’t have enough substitutions for "L" and went back over his work to muddy things up later on.

L3 isn’t substituted until the fourth row. That might be funky/deliberate shenanigans by the author, but there’s also the possibility that he only had 2 homophones for "L" when he first started then went back and filled in some of the L1s to make things more confusing.

If he did that then he’s have 1212121212121211211…etc. It’s like everything he did is perfectly designed to make his encryption behavior ambiguous.

That’s part of the reason I’m so upset about [SLOI]. As far as I can tell, there are like five or six plausible explanations for why this mistake was made and all of them have major problems.

That’s really interesting. I wonder what’s up with L, you may start to think he wanted to give a hint.

You know, I’ve been wondering about that myself. It is insane how many times he uses the trigram [ILL] in the cipher. [KILL] shows up 4 times, [WILL] shows up 4 times, and he’s also got [THRILL] in there. Those words are like 8% of the entire cipher and the result is that the plaintext sounds extremely dumb. He has every possible permutation of the word [KILL] except for present tense. I’m frankly surprised that he didn’t throw [KILLINATION] or [KILLOCITY] in there. It feels like a joke, but I don’t know. Maybe that’s just how the guy talks. The plaintext does sort of feel a bit like trolling, though.